Archive for May, 2009

Chord Progressions: Making People Feel Something

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Writing on May 30, 2009

I always wince when industry execs refer to songs as being emotional…as in ‘let’s hear that first song you played again, the one with the emotional chorus.’ Correct me if I’m wrong, all music is supposed to make you feel something. But what they’re getting at is songs that become the biggest hit singles often have an extraordinarily strong emotional pull.

Melody and lyrics are critical when it comes to emotional pull (and in my opinion a talent for melody is the one thing that a person can’t be taught) but well-written chord progressions are key, and the importance of the series of chords chosen for a song is overlooked by many new writers.

Sitting down with the piano or guitar we often believe that whatever chord changes first came to mind are the foundation of the song; that it’s unchangeable and the task is now to write some words and melodies over top. However in truth you can manipulate the chords under a vocal just as readily as you can manipulate the melody: remixing often involves doing just that. When you stop automatically trusting whatever chords you happened to pick out of the air, you begin to have some control over how the song makes people feel. This is what people refer to as songwriting ‘craft’ and it’s part of getting professional about your writing.

Without getting too far into the dry wasteland that is music theory, here’s a way to open up your writing.

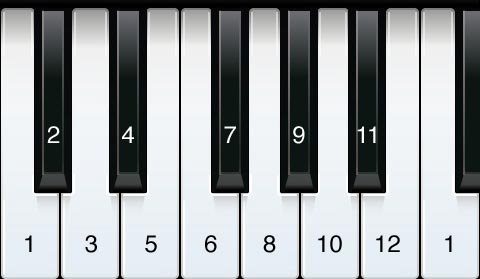

If you sit at a piano and play chords up the scale of C Major, this is what you’ll get:

Position 1 = C major

Position 2 = D minor

Position 3 = E minor

Position 4 = F major

Position 5 = G major

Position 6 = A minor

Position 7 = B diminished

When most people begin writing, they’ll try something basic like alternating back and forth between two chords, say Position 1 (C major) and Position 4 (F major), and they’ll go with that as their verse or chorus. Simple progressions that sound good to our ears tend to become the standbys we go to unless we challenge ourselves. I’ve noticed that some people believe you can only move a step at a time in either direction…creating chord progressions like 1, 2, 3, 2. You can jump all over the place, and you should.

For years I was in the habit of only using the 7 chords readily available in the scale. Until I was shown, I didn’t realize that I could, for example, play a progression like 4 (F major), 5 (G major) and then a minor 5 (G minor, which is not naturally in the key of C) and then 1 (C major) without the earth caving in. In fact, go ahead and move to any chord from where you are. You can move from position 1 to position 4, but use an F Minor instead of an F Major. Or you can play a C Major followed immediately by a C Minor.

When you let go of the scale you’re in and allow yourself to see all 12 notes available on the keyboard you realize that at any given moment, from where you are, there are 23 other basic places that you can go. (The major and minor chords of all 12 notes, minus the chord you’re already on.) Sometime, when you’re sitting at your instrument with no inspiration, I recommend jumping around between chords for a while as a way of opening up your writing. Some of the jumps you’d normally never think to play can spark a feeling you know from other music, but didn’t know how to evoke yourself…and you can find yourself writing a song around the device you’ve just discovered.

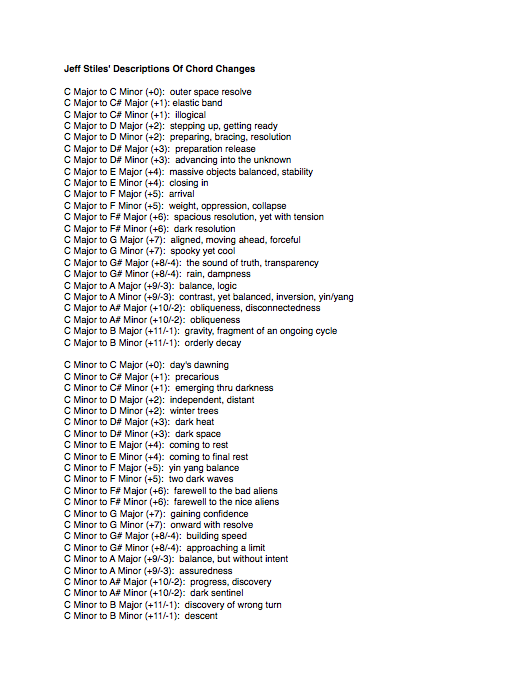

A few years ago I did an experiment with some friends who write. We all separately played C major followed by C minor…and then wrote down a description of how that chord change felt. Then we did C major followed by D major, and all of the other possible jumps moving up the keyboard.

Put side by side, many of our written descriptions described similar emotional responses. Some images that kept showing up were the feeling of ‘stepping up or down,’ (fairly obvious for standard incremental movements along the keyboard like C major to D major); ‘precarious balance’ (for less standard incremental movements like C minor to C sharp minor); ‘optimism’ or ‘pessimism,’ (when the chord change involved changing between a major and a minor); ‘assuredness’ (a common jump like C major to A minor); even ‘planetary’ feelings (for odd longer jumps like a C major to F-sharp minor, which are obviously used in lots of space movies).

So it looks to me like, either by nature or nurture, we feel chord progressions in similar ways. When you’re writing at your instrument and what you’ve got feels okay but not great, I encourage you to challenge one of your chord changes by trying the 22 remaining possibilities. If you do this often enough, you’ll develop a strong command of the emotions you bring as the listener moves through the song with you.

Hard Cuts, Beat Mixing & Train Wrecking: The DJ As Performer

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing on May 21, 2009

It’s difficult for an audience in a club to know exactly what the DJ is manipulating at a given time and what’s already part of the track they’re playing. Too often I’ve heard someone on their way out of a club crying ‘the way that DJ remixed the new Britney was fiiierth!’ (or some variation) making it obvious that they believe DJs ‘remix’ songs on the spot, creating a new version of a song by laying an acapella over another track that they’re creating live. Nine times out of ten what’s happening is the DJ is simply playing a remix a producer slaved over in the studio for a few weeks…it’s just a remix that particular club-goer hadn’t heard before.

There are exceptions. Joe Claussell is a New York-based DJ who constantly manipulates the music he’s playing. He’ll often have a drum track looped while he twists a knob on his mixing desk in quick rhythmic stabs, teasing the crowd with chopped-up, filtered hints of a vocal track before bringing it in fully.

In Toronto, Deko-ze is a DJ I’ve watched keep four tracks running simultaneously, mixing and matching elements from all of them, looping a beat on a CD deck in front of him while reaching off the to side to nudge a record like a plate spinner sensing the need for a slight adjustment.

Some laptop DJs running Ableton Live are able to perform in a similar way because the software has the flexibility to loop a section of one track while the DJ chooses sections of other tracks to bring in, however the need to develop the physical skill of matching the speed of two tracks is eliminated because the software does it for them.

What the audience needs to understand is that a DJ spinning vinyl or CDs cannot separate individual parts of a track unless they’ve been supplied individually on a single or a bootleg. In other situations the best they can do is filter out the bass in a track to clear away some drums and expose the vocal a bit more, or filter out the treble to do the opposite. DJs that are acrobatic enough to have 2, 3 or 4 tracks spinning simultaneously are often layering drums on CD decks (they’re able load a perfectly looped section into memory), adding an acapella they obtained somewhere, and possibly adding musical elements from an instrumental mix of another track. It’s possible to go back and repeat a section of a vocal, or something relatively simple like that, but it’s difficult to apply rapid-fire effects to a vocal. Often you’re hearing something that’s on the acapella already, or the DJ has done some preparation of the track at home first.

What the great majority of DJs do is play one track after another, and the only time more than one element is being heard at the same time is while the DJ is fading from one track into the other, making use of the drums-only intros and outros tacked onto virtually every club track available today. Essentially, club tracks are designed like Lego blocks. The next one snaps onto the last one in most any configuration. It’s known as ‘Train Wrecking’ when a DJ messes up by letting two drum tracks get out of sync with each other while fading from one track to another…because, ostensibly, it sounds as messy as a train going off the tracks.

Club audiences have splintered into as many genres as house music has fractured into. And a DJ that only needs to play one genre, like dubstep or electro, doesn’t have to worry too much about the tracks they play being wildly different in tempo, rhythm or sonic range. Within this realm, the difference between a good DJ and a bad DJ is their taste in tracks, and their ability to read a crowd.

On the extreme side of DJ laziness is Israeli superstar DJ Offer Nissim, who is rumoured to put on a full-length CD created in the studio beforehand and pretend to mix all night from one track to another, collecting a $20k cheque at the end for showing up and ‘performing’!

In the early 90s, when turntables were the only sound source and DJs would begin a night with R&B and rap, progressing to house and eventually hard techno by the end of the night, the DJ had to work hard to learn what worked and what didn’t. Those turntables didn’t have as wide a pitch adjustment range as technology offers now, so beat-mixed music would have to change tempo incrementally over a few tracks.

Some all-but-lost creative mixing techniques include ‘braking’ (hitting the Stop button on the turntable to slow one track dead and then starting the next one, a technique used to start a set in a different tempo) and the ‘hard cut’ (where a DJ would surprise the crowd by cutting from one track directly into another). Hard cuts were sometimes necessary because tracks didn’t always begin with long drum intros…keyboard or acapella intros were acceptable on a 12″ version and this required the DJ to get a little creative.

One of my favourite creative mixes exists on a mixtape made by Toronto’s Patrick ‘D-Nice’ Hodge in 1992. It’s somewhere between a regular crossfade and a hard cut:

At 0:23 the piano riff that comes in is from the next record, ‘Back To Me’ by Ubiquity. This riff is in the same key as the previous record, and it works beautifully with the existing chord progression we’ve been listening to. At 0:31 he drops the first record entirely, as the beat comes in on the new record. The fact that he recognized these two records in his crate would work together in this way is one of those happy accidents that happen increasingly often the more attuned a DJ gets to his material. The second track coming in, by the way, is just slightly flat, because at that time in order to line up the tempo of two recordings, the original pitch of the recordings would slide around as necessary. That’s no longer an issue with CD decks and laptops.

I still don’t know what track Patrick was mixing out of here. If anyone can identify it, please hit me with an e-mail.

Continuing back in time to the mid-70s when DJs like Tom Moulton in New York discovered disco’s relentless ‘4-on-the-floor’ kick drum pattern, the concept of beat-matching two tracks while mixing from one to the other was born. It’s worth mentioning that at that time there were even greater physical challenges for the DJ. Most of these tracks were not recorded at a stable tempo, so the DJ was constantly adjusting the turntable to keep the beat aligned, especially if they were trying to keep two songs running together for more than a few seconds. DJ turntables with convenient pitch sliders and robust tonearms/needles hadn’t been developed yet and neither had 12″ singles with extended versions that had long drum breaks for mixing.

Moulton was reportedly the first DJ to make long versions of his favourite songs by editing them on reel to reel tape and bringing the machine to the club that night. Some of his re-edits were later released by the original labels. I also have it on good authority that at Studio 54, staples like ‘Come To Me’ by France Joli would be extended manually by the DJ by mixing back and forth between two copies of the same record. DJing was a highly physical act at the time, and within the technical limitations there was quite a bit of creativity going on.

Addiction: Fred Everything ft. Wayne Tennant – ‘Mercyless’

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing, Production on May 19, 2009

Wayne Tennant was the lead singer of Toronto funk band God Made Me Funky, then he moved to Montreal, started recording some solo work and spent some time playing Morocco and recording in the UK.

He’s done a collab with Montreal deep house producer Fred Everything for Fred’s album ‘Lost Together’ (Om Records). The track is called Mercyless…the single hit #2 this week on Traxsource…the only soulful house online store that matters. Tastemaker DJ/producer Osunlade also has it in his top ten right now.

Here’s a sampler of the mixes on the single. In order: the original LP mix, then the deeper Fred Everything & Olivier Desmet Remix, then the smooth AtJazz remix.

It’s a slow-burn. I liked it on first listen…I was addicted to it after a few. Wayne’s solo EP is coming out this summer.

Pan & Throw

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing, Mixing, Remixing, Singing on May 19, 2009

This blows my mind every time I listen to it:

What you’re listening for is a 16-bar section toward the end of ‘Luv Dancin’ by Underground Solution…circa 1991. Classic house music on the legendary Strictly Rhythm label. The main hook of the track is a female vocal sample from Loose Joints’ disco classic ‘Is It All Over My Face’. There is a version with a full female vocal as well. But there’s a male vocal snippet from the Better Days Remix of Carl Bean’s ‘I Was Born This Way’ weaved into the tapestry and in this part of the extended version the producer decides to riff on that sample for a minute before winding down and man it gets me every time.

It’s partly the sample itself. It’s got that gospel depth to it…he’s feeling that shit…and the way he ends his phrase, trailing down, to a gritty release…there’s tragedy there.

But there are also choices that the producer and/or mix engineer made: the sample pans left and right, sometimes it’s ‘dry’ (no effects), sometimes there’s a delay throw (certain syllables echo) and sometimes there’s a reverb throw (a big roomy sound on it). The patterns entrance me. So simple, yet so complex. So inspired, so not systematic. I could loop those 16 bars all day.

Jane Siberry On Art, Science & Love

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Writing on May 19, 2009

Her voice is often considered quirkily annoying by casual listeners, and in the early 90s, shortly after the career stride of being invited to work with Brian Eno at Peter Gabriel’s RealWorld studios, she played a festival in England and her quirkiness got her booed off the stage. And, in the mid-90s I collaborated with her, shattering all illusions that my high school idol was a person I would want to be friends with.

However.

She was not only a guiding star for me in high school (living in Ottawa but wishing I was safely in her Toronto) but when I go back to her output from ’84-’94, it was quite a contribution to music. Much of her earlier stuff was analytical and humorous, full of casual commentary on art, science and psychology…running with what Laurie Anderson started. When a more serious, personal song appeared in the middle of an album it was surprising that the same person who just discussed the symmetry of atoms in a molecule, or the purpose of non-dancers taking dancing classes, would in the next breath express the bare pain of a breakup.

In ‘You Don’t Need’ she gets poetic, exposing her inner Robert Frost: ‘so I walk on through the marshes and my cheeks are burning white, and my hood is your rejection and my pain is your connection…and a bird I don’t recall called don’t recall called don’t recall…and I know you must be there because people stop to talk to you…you don’t need anyone to want you, don’t want anyone to need you and I think I have yourself almost convinced I have yourself almost convinced…so I ate a star from the far back black sky and it floated up behind one eye and wavered there.’

In the mid-80s, her refreshing, highly conceptual live show was a total girl-fest. It featured three female background singers whose abstract miming was loosely choreographed, and it seemed to be a requirement that they match her oddly wavering vocal style. When the four of them wavered together, it was like four flickering candle flames that synced up unexpectedly for breathtaking moments of harmony, like in the live version of ‘Map Of The World (Part 1)’. There’s a brief reference to Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hey That’s No Way To Say Goodbye’ in the middle of this version, and the payoff comes as the womens’ voices fan out together in a beautiful chord.

After 1993’s ‘When I Was A Boy’ for Reprise records (which included her collaboration with Eno), songs found placements in films and TV shows; Siberry cut a jazz album; she parted with the U.S. major and formed her own indie, Sheeba Records; pioneered pay-what-you-can/’self-determined’ pricing for internet downloads before Radiohead did it; sold signed stuffed rabbit dolls online; disposed of the majority of her earthly belongings including her house; changed her name to Issa Light and continued recording, sessions funded by fans.

Press on sister.

Like A Needle In A ‘Reckerd’ Groove

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Singing on May 18, 2009

Further to the idea of micromanaging each syllable a singer utters, I want to point out that the natural way we pronounce words when we speak isn’t always the best way to pronounce them when we sing.

Why did Mick Jagger, and the great majority of all British rock’n’rollers from the get go, lose their limey accents and sound convincingly American when they opened their mouths to sing? It’s so common that a lot of us think it’s impossible to sing any other way. And yet Lily Allen retains every bit of her Britishness on record. It’s a choice.

And if a singer doesn’t make cool and pleasant choices–naturally or through trial and error–sometimes a producer helps them along.

In 2000 a young female R&B singer was signed to an American major label cutting her first album and a friend of mine was producing. One of the phrases in the chorus was ‘like a needle in a record groove’. In the girl’s natural speaking voice, she pronounced the word ‘recorrd’. Her sung pronunciation was more like the cooler and often-used ‘rekkid.’ But the producer asked her to sing ‘reckerd,’ because in the context of the song it the coolest choice: more retro, and therefore more current.

Don’t kid yourself…choices like this are made at the microphone every day. Whether the result is an honest representation of who the artist actually is, or more a persona the producer is designing, the identity of the artist on the final recording has to be likable! If the vocalist doesn’t make good choices naturally upon opening their mouth, the producer is left with no other choice but to instigate experimentation of this kind.

Cashflow In The Music Industry

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Publishing on May 18, 2009

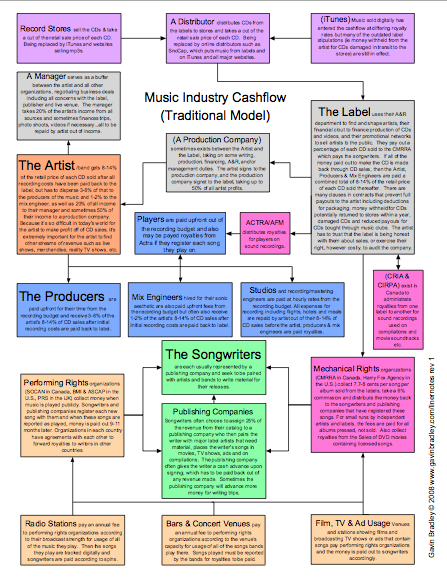

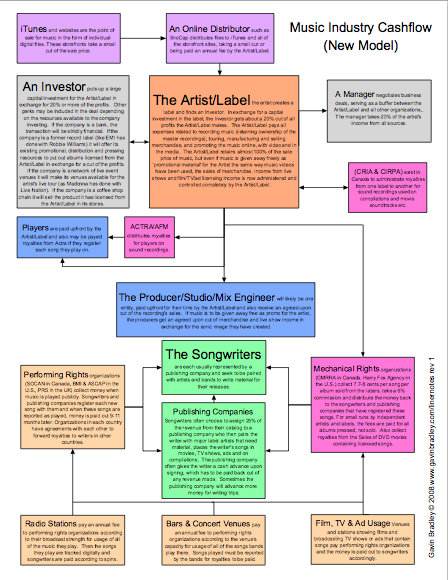

The industry is huge. There are all sorts of organizations that funnel royalties down to artists, writers and producers. I couldn’t keep it all straight in my head, so I finally made a couple of flowcharts.

One flowchart illustrates the traditional flow of cash, and the other gives some shape to the new model that we see forming, wherein the major labels are replaced by investors (of any kind) and each artist releases their material digitally on their own indie label. Right-click or Control-click (Mac) to download a legible PDF.

I recommend reading these from the top left corner. That way, your eye will guide you through the information in a way that makes sense. Colour coding is by ‘branch’ of the industry (income from sales of recordings, income from performance of songs etc.).

This is a work in progress. If there are errors or omissions, by all means let me know. For example, booking agents will be added in the next iteration.

Joe Williams Siiiiiiings It

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Singing on May 17, 2009

I was never much into the blues because–although I recognized it was the forefather of jazz and rock’n’roll, and that, rooted in slave songs, it had this ingenious function of taking misery and flipping it into light commiseration–it struck me as overly macho and formulaic.

When I was a kid an older jazz freak friend loaned me a disc by Joe Williams and it was okay, but at the time I preferred Miles Davis and John Coltrane to most vocal jazz. Then a few years ago I found ‘Count Basie Swings, Joe Williams Sings!’

It’s a collection of blues songs…but Williams’ masterful interpretations are backed by the searing hot jazz of Basie’s big band. Although it’s hard to imagine now, this pairing must have been a modern, daring concept in 1958 akin to the idea of a hard techno remix of an R&B song in the mid-90s.

The master tapes for the stellar first side of the LP went missing, so the first four tracks on the CD version had to be salvaged from the original vinyl master. The pops and clicks of vinyl only add to the nostalgic quality.

It’s difficult to explain just how masterful Joe is as a singer, because it’s hard to separate his god-given vocal capabilities and his own inventiveness. He’s a baritone with a crazy low range, but he’s also effortless and clear in his high falsetto…with a quirky sibilance on top (his pronunciation of the consonant ‘s’).

All good singers have a command of their tone, resonance and breathiness at a given moment, but he seems to have full command of the degree of raspiness he introduces, and the lilting effect that happens when people go up into their falsetto mid-syllable…both things that tend to be happy accidents for other singers.

Often he’ll change the swing of his delivery on a dime, leaving the band playing ‘straight’ behind him while, after establishing the rhythm of the song, he suddenly swings his vocal in a new, unexpected way. And sometimes he’ll change it again before the song is through. I don’t think I’ve heard this done in quite this way before or since Joe Williams. On this record he’s got personality to spare…in the way he pronounces the word ‘love,’ for example on ‘The Comeback,’ when he sings ‘girl you know I looohhhhhhve you’…and his ad libbed ‘do not you feel mighty lonesome’ (as opposed to ‘don’t you feel mighty lonesome’) on ‘In The Evening’. The man is just cool.

But the piece-de-resistance in his bag of tricks is his ridiculous lung capacity. I love it when he shows off at the end of both ‘In The Evening’ and ‘Every Day I Have The Blues’ by holding notes long enough for you to make a five-course meal, eat it and wash the dishes.

Though it’s unthinkable these days, each of these recordings were made in one continuous take. Since these musicians cut their chops playing live for decades, I’m sure it was natural to get a take that was close to perfection after a few tries. But it seems like Joe had a knack for taking any vocal imperfections that surfaced while the red record light was on and riffing on them, playing with them to make them into an asset of that particular performance. Again, it all seems within his control, so no one will ever know what moments were accidents.

Joe appeared on a few episodes of the Cosby Show as Claire Huxtable’s father. Before he died, in ’99, a journalist friend of mine met him at a club in NY in ’99, and I’m told that Joe had one hell of a high opinion of himself. Modesty and humility are attractive qualities, but I hate to say it: I agree with Joe’s on this one.

Emotional Utterances

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production, Singing on May 15, 2009

Some singer, at some point, must have naturally began adding a breathy ‘h’ to the ends of words. And some producer must have heard it and realized that this makes singers sound like they’re getting emotional. And when a listener hears the singer getting emotional, they in turn get emotional. That’s good for business, when you’re in the business of making people feel!

I’ll show you what I mean…check out Kelly Clarkson adding a big ‘h’ to the end of almost every line in the first verse of ‘My Life Would Suck Without You’. I’m using the Chris Ortega mix because the vocal is upfront:

This reminds me of the way marketing has developed into a science in the 21st century. Less gut and more tried-and-true, market-researched technique. Producers, myself included, are hyperconscious of ways that we can bring emotion to a song by manipulating the singer’s performance on a syllable-by-syllable basis. (That’s if the singer doesn’t already do it naturally.) It’s pretty much on the checklist that’s been created by the Idol franchise for what a good singer needs to be able to do. At the McDonald’s of the music world, they ask ‘would you like breath with that’?

Hey, it works, and there’s nothing wrong with it…but I prefer it when emotional utterances come out naturally in the performance rather than being pulled from a palette of what we now know works. I’m sure Otis Redding didn’t pre-meditate what he was going to utter in between syllables…even if he became aware of his own arsenal of signature vocal tricks. Do we know a bit too much now about how things work? When you’re really feeling what you’re singing, you don’t have to design how you’re going to deliver each part of it.