Archive for category Singing

Sade As Wounded Warrior

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production, Singing, Writing on March 18, 2010

It hurts to write a single sour word about Sade. Being a lover of music in many disparate genres it’s difficult to play favourites, but over time I’ve come to realize that Sade does hold the Best Artist spot for me. Against much more obvious competition, ‘The Sweetest Taboo’ has unexpectedly landed as my favourite song, and 1985’s ‘Promise’ would be the album I’d take to a desert island.

She, the woman, and they, the band, have come to represent high taste and integrity in music. They’ve built a trust in their fans that the product will be filtered and distilled before it reaches us: there is no chance for cheapness to get through. Much of their music has been slow-burn: it takes time for such subtle grooves and sparse melodies to get under the skin. The last few albums of new material, each released in a different decade, have been increasingly moody and subtle–increasingly less immediate, but with a satisfying payoff after repeated listens. Although Sade has never professed to be a vocal athlete, the band is always on point and the ambiance she brings with her cool presence makes them one of the few live acts that I cannot miss. With a 10-year gap since their last studio album, curiosity and expectations were high. I put off writing about the band’s new album, ‘Soldier Of Love’ for several weeks in order to digest it and give it a fair shot.

Sade has allowed unprecedented media access this time around, and in the course of it much has been made about her previous insistence on privacy. She shook hands around the room at the NYC album listening party, performed the single on every major talk show, and satirized herself in a guest appearance on the Wanda Sykes show. Articles like this one in the London Times have combined historical context with personally revealing interviews. Soundbites from a recorded interview were made available here. A short film surfaced discussing the making of the album, and then another appeared about the making of the first video.

Sales have been excellent, indicating that the band’s following is still a faithful army in this day where the pirate download has become standard. The album went straight to number one on the Billboard chart and held strong, proving strong radio action is not required to sell such a trusted band these days.

So is the new disc good? It is. I’m afraid to say however that it’s not phenomenal, and certainly not groundbreaking or revelatory.

Let’s do a little bit of history. The band began as a live jazz outfit. 1984’s ‘Diamond Life’ was made up largely of songs they’d already been playing around London, including most notably their throwback anthem ‘Smooth Operator’. Robin Millar produced, beautifully packaging their organic jazz café sound, a sound which spun out into a movement in 80s England with bands like The Style Council and Simply Red filling out the genre. In the first few videos a narrative was built around Sade as a jazz-club diva mixed up in a gangster plot. Album tracks like ‘Frankie’s First Affair’ and ‘Sally’ brought seedy, urban characters to life. ‘Hang On To Your Love’ and ‘Your Love Is King’ were classic, universal love songs.

The band’s follow-up, ‘Promise,’ arrived just a year later with the melodically sweeping first single ‘Is It A Crime’ continuing the torch song tradition. ‘The Sweetest Taboo’ was a light singsong with darker lyrical undertones, built around a highly original syncopated kick-and-rimshot pattern not heard in music before or since. ‘You’re Not The Man,’ another stunning jazz ballad, only appeared on vinyl as the b-side of ‘Taboo’; it was thankfully included on the non-vinyl versions of the album. ‘Maureen’ and ‘Tar Baby’ were again character pieces, but this time Sade took a page from her personal life, singing about her best friend and her grandmother. The first hint of sequenced electronics appeared on ‘Never As Good As The First Time’ and a quick scan of the album credits reveals that this was one of the band’s first forays into sharing production duties with Robin Millar. It was the first sign of a departure they were about to take.

While it’s easy to see that most of their early material was built around elaborate, classic melody, ‘Never As Good’ is a groove-based song. Sitting somewhat conspicuously next to fully organic songs on the album, the drum machine loop and percolating synths settle us into a hypnotic groove, and the verse vocal weaves itself rhythmically into that groove, the melody flipping between two neighbouring notes. It is a different way to write music: it comes from the opposite angle, building on a rhythmic foundation rather than a melodic one.

There was a 3-year break. When the band returned with ‘Stronger Than Pride’ in 1988, they had taken over production duties from Millar, who, tragically, had gone blind from an inherited retinal disease during the recording of ‘Promise’. The jazz influence had faded, echoed only on the horn arrangement in ‘Clean Heart’. It was replaced by the band’s own unique R&B sensibility. Most importantly, they were favouring this new approach of writing over programmed loops, and here I believe is where Sade’s melodic and lyrical approach began to change from the lighter character-based storytelling of ‘Sally’ and ‘Maureen’ to a longer, drawn-out process of feeling around for the singer’s own subconscious undercurrents. There seemed to be a belief that the lyrics needed more sombre depth to them, more of a message.

1992’s ‘Love Deluxe,’ and 2000’s ‘Lover’s Rock’ furthered this direction, forging original works over many different feels and grooves. Unlike the big jumps on the first two albums, melodies generally fluttered between a few neighbouring notes, except on the more commercially viable songs ultimately chosen as lead-off singles (‘No Ordinary Love’ and ‘By Your Side’ respectively).

And now ‘Soldier Of Love’.

Despite the band’s insistence that they work hard not to repeat themselves, for the first time I feel there is a degree of repetition going on here. The title track bites chord progressions from ‘No Ordinary Love’ and melodic bits from ‘Somebody Already Broke My Heart’. The bouncing tambourine in the drum groove on ‘The Moon And The Sky’ also recalls ‘No Ordinary Love’; the rhythm track on ‘Skin’ recycles that of ‘Cherish The Day’. After ‘The Sweetest Taboo’ and ‘The Sweetest Gift,’ the title ‘The Safest Place’ looked oddly familiar in the track listings. It is also the obligatory beat-free moment on the album–a tradition that began with ‘Fear’ on ‘Promise’ and carried through, one track per album, with ‘I Never Thought I’d See The Day,’ ‘Pearls,’ and ‘It’s Only Love That Gets You Through’. If they were putting out records every two years, these similarities wouldn’t matter so much. But considering we’ve just had the longest gap between releases, I would have loved to see the band forge new paths rather than rely on old habits.

Once stating that timelessness was one of the mandates of her writing, Sade’s first lapses in taste have now happened: the cheap reference to Kool Moe Dee’s ‘Wild Wild West’ on the ‘Soldier Of Love’ single, perhaps meant to show light irony; the reference to ‘Michael, back in the day’ layered with a simulated MJ holler behind it on ‘Skin,’ likely included to acknowledge the loss of a personal hero; and a few somewhat embarrassing moments in ‘Babyfather,’ beginning with ‘she liked his smile, she wanted more, the baby’s gonna have your eyes for sure.’ The idea of including Sade’s daughter Ila and bandmate Stuart Matthewman’s son Clay as a childrens’ chorus on ‘Babyfather’ points toward a lapse in judgment due to unchecked parental pride. It is unfortunately likely to be the second single because it is the only light storytelling moment on the record, and there’s not much else with an obvious radio hook.

Production- and writing-wise there are some developments on the disc. A blues influence–something we first heard in the band’s cover of ‘Please Send Me Someone To Love’ on 1994’s ‘Best Of Sade’ collection–has emerged more strongly here on ‘Long Hard Road’ and ‘Bring Me Home’ among others. The reggae influence of ‘Lover’s Rock’ has deepened in the form of dub basslines peppered through the album and some lush three-part harmonies reminiscent of The Wailers on the bridge of the ‘Soldier Of Love’ single, which also boasts the new sonic colours of army battery drumming, futuristic synth effects and one ferocious hip hop snare. I welcome back Stuart Matthewman’s saxophone lines after their absence on ‘Lover’s Rock’. Upon sitting with the record, ‘The Moon And The Sky’ seems as though it will be one of the songs that will deepen with time. ‘Morning Bird,’ while cryptic and mournful, is exquisite and feels like the gentler moments of the 1996 Sweetback album (the band’s side project without Sade). ‘In Another Time’ feels like lazy writing, full of melodic gaps, but lyrically it is special in the way it captures a mother-daughter advice session.

There is a sentiment of sombre fortitude or bitter resolve present throughout the album; a running theme of being a soldier (the title track) or warrior (the closing track). The rest of the songs tend to lament loss or to wearily offer encouragement. I’m not sure whether this darkness reflects where Sade is at personally, or whether she feels it is only worthwhile to document the heavier things inside her, because the writing itself also feels quite laboured to me. One of her gifts as a writer has been her ability to reach in and describe a feeling directly or metaphorically, yet without a trace of cliché…case in point: the phrase on ‘Be That Easy’ where she states both simply and profoundly ‘for I am a broken house, I’m holding on a broken bow’. However I believe she has become fixated on this one particular gift rather than using her complete palette: for a very long time the songs have not been melody driven and they have not included those narrative stories less related to her personal demons and philosophies.

In the ‘Making Of Soldier Of Love’ footage–the first time information has been let out about the band’s creative process–there is a lot of talk about the ‘struggle’ involved in the writing process. The band and Sade herself express, wearily, an exhaustive search that goes on in the writing of each song. She explains that she stays away from the studio for long stretches of years because it’s such a commitment to go in and make an album. She sighs with the heavy weight of her own expectations that the music be built on truths and constructed with love. She flips through a stack of papers several inches thick saying ‘look how many words, look, all of this, it’s one song,’ revealing that there are endless rounds of adding and chipping away at words in the search for the right ones.

She analogizes her process: ‘once I start working on a song I sort of feel I’m on a boat, and the boat knows which way it’s going…sometimes the boat will go off course and I have to fight to steer it back.’ Also, ‘the three minutes where the song really comes together in that moment where it sort of arrives from the ether or wherever, then the rest, a lot of the rest is working on maintaining the spirit that came to you from no will of your own, and that’s the difficult part…being loyal to the original vibration and spirit of feeling that came with that song.’ This struggle, I feel, is a process Sade has put on herself, and in my experience it’s what would produce the heaviness, the laboured feeling of the music. While this gradual syphoning of the subconscious–of connecting to the ether without staring it down directly–is not an uncommon approach and it is valuable for some songs, we also know from her earlier work that she’s capable of balancing out this heaviness by writing sweeping melodic stories off the cuff.

And this is really what I want to say about the new album: it may be that Sade now goes into the studio simply trying to initiate the purge she believes is expected of her. In that way I believe she’s gradually misconstrued, by small degrees, what her job as a musician is. At the other extreme we have artists that push the boundaries as far as possible with each new album to break out of the shell of what’s expected. I feel the best work happens somewhere in the middle, in a space when original ideas are allowed to flow naturally with little reaction to what’s worked before. And the best songs seem to come when the conscious mind vaguely teases the subconscious out, but it is not always helpful to approach the studio expecting drawn-out martyrdom. I want Sade to have fun writing the music she presents to us.

People In Your Neighbourhood

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Singing, Writing on July 15, 2009

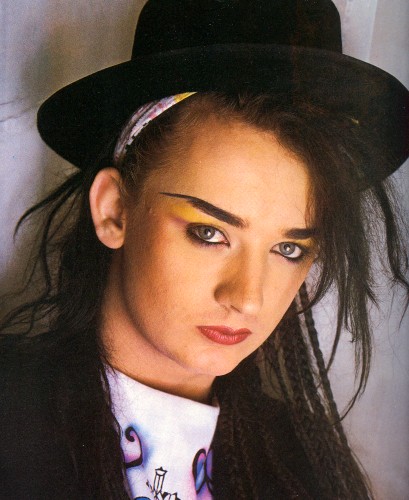

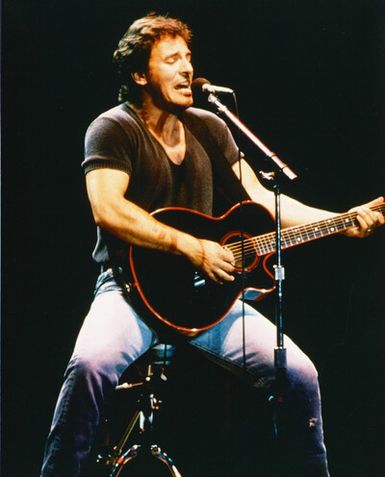

At the height of Culture Club’s success I remember people complaining that Boy George should have been able to make it solely on musical talent, without needing to resort to gimmickry…ie dressing in cosmopolitan drag. He was a talented writer and singer, but–consciously or unconsciously–he realized that audiences are not attracted to artists purely on the merit of their musical output.

We know this is true because there are endless examples of uniquely talented musicians that never garner a substantial following. That’s because what actually attracts us, as listeners, I believe, is an artist’s identity.

It’s true that this identity is built in part around the style and content of the songs, including the lyrics and the overall tone/sentiment. But for a star to be born, it’s critical that the music align properly with a host of other attributes, including the voice they were born with and the way they choose to use it; the physicality they were born with and how they choose to dress it up; how they move; and how they interview. The persona constructed with these tools needs to be instantly recognizable and compelling. (I won’t go so far as to say ‘appealing’, because there are plenty of celebrities that we love to hate.)

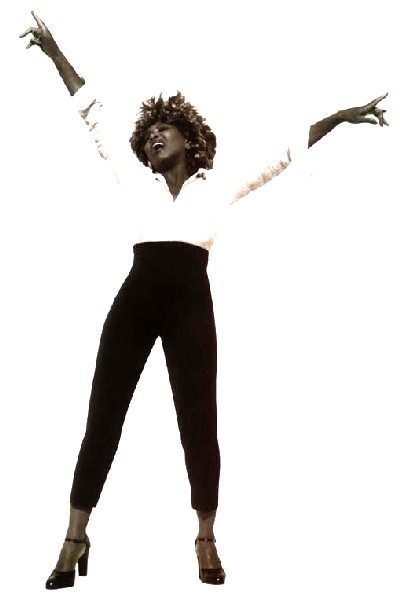

Speaking recently of the Supremes, Diana Ross wasn’t the lead singer of the group because she had the best voice in a technical sense. But her effervescent look and pastel-sounding voice combined to make her a compelling figure: she had instant identity.

Whether it’s the first few lines of a song, or a photo in a magazine spread, the audience needs to get a sense of the artist’s identity similar to the impressions we form of the people in our neighbourhoods we see around but haven’t had personal conversations with yet.

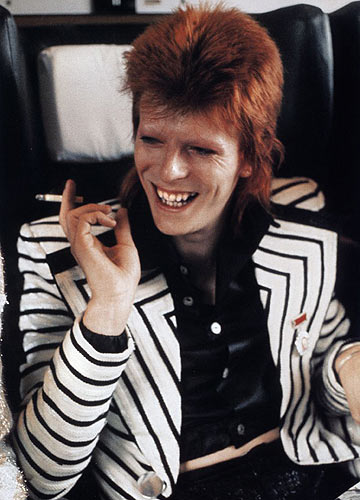

Here are some artists with identities so clear and compelling, whether we like them or not we all feel as though we know them from around.

All musicians are driven to make music. Those that are also driven to author every aspect of their public persona–from clothing to video treatments–end up having a lot less time to sleep but they have an edge over the rest, both in terms of career control and potential for success. That’s because most of us lack the ability to stand back and get a clear perspective on who we are, pinpoint what’s compelling about ourselves and amplify it.

Those who can’t must rely on industry executives’ abilities to look inside them and tailor the right persona…a rare feat in itself. If they get it wrong, the project will fail either because the identity won’t be compelling, or the artist won’t be able to carry an ill-fitting persona for very long before the audience sees through it.

The Cold-Warm Effect

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production, Singing, Writing on June 18, 2009

After the sound of monophonic synthesizers, played by hand one note at a time, became commonplace on progressive rock recordings in the early 70s…

After people got used to hearing tapestries of synths triggered like clockwork by unfeeling sequencers and arpeggiators in the experiments of Kraftwerk through the mid 70s…

And after producer Giorgio Moroder pulled late-70s disco into the future by placing Donna Summer’s operetics over a pulsing synthetic backdrop on ‘I Feel Love’…

…Alison Moyet belted ‘Goodbye 70s’ over Vince Clark’s minimal synth and drum machine programming on Yaz’s 1981 debut album ‘Upstairs At Eric’s’.

Clark, the keyboard player and chief songwriter for a fledgling Depeche Mode, left the band after their debut album and formed Yaz (known in the UK as Yazoo). Clark’s working relationship with Moyet also imploded early on, leaving just two beautifully crafted Yaz albums. The detached lyrical attitude was new wave and the melodies were pure pop, but the juxtaposition of the warm human soul in Moyet’s ferociously large voice over top of Clark’s frigid production was a new level of what I call ‘cold-warm’ production.

‘Midnight’ is a great example of this style. After a naturally-paced acapella intro, the synth sequence begins without drama or fanfare. Emotionless and ruthlessly precise, it’s there solely to do the job of defining a framework of chords and rhythm under her voice. Her delivery is suddenly recontextualized: because the backdrop is icy cold, the heat of human breath against it is that much more apparent.

After Yaz, Moyet began a successful solo career and Clark formed Erasure with Andy Bell–whose vocal tone, it has been noted, is curiously similar to Moyet’s.

Enter Eurythmics. Dave Stewart and Annie Lennox had been making music together for some time, first in rock band The Tourists and then as Eurythmics, releasing their experimental but mostly organic (ie non-electronic) debut album ‘In The Garden’ in 1981.

But then they clued in on where Yaz, and other UK synth-based bands like The Human League and Heaven 17 were going and jumped in on their seminal ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)’ album in 1983.

The liner notes on the 2005 reissues of the Eurythmics’ catalog discussed which drum machines and synths had been used, and also revealed that organic sounds–like drumming on glass bottles–were routinely weaved in. However, these were treated with effects so as to be camouflaged as part of the cold electronics. A manifesto of the pair’s directives was written on the wall of their studio, including the phrases ‘Tamla Motown,’ ‘Electronica’ and ‘Coldness’. So there it is: soul on ice.

On their best work–the fully electronic ‘Sweet Dreams’, ‘Touch’ and ‘Savage’ albums–Lennox’s soulful voice is generally the solitary human element sitting on top of the coldness. She even sonically evokes the visual of her warm breath meeting wintery cold in her trademark practice of peppering vocal performances with gutteral stabs of exhalation. Very occasionally another warm melodic element is chosen to create that same contrast against the pings and bleeps: the long trumpet solo on ‘The Walk’ and the violin lines of the British Philharmonic Orchestra on ‘Here Comes The Rain Again’.

‘Love Is A Stranger’ is a 3-minute pop song with a perfect balance of soul and circuitry.

Lennox pushed her experimentation with coldness further by developing a suitably cold image. Often labeled androgynous, I believe her main character, sporting an orange crew-cut, would be more accurately described as inhabiting a deadened sexuality. After having established that baseline, she was then in a position to play with the hypermasculine (dressing up as Elvis in the video for ‘Who’s That Girl’) or the hyperfeminine (her female character in the same video, or the split-personality cougar depicted on the ‘Savage’ concept album) as a way to critique, humorously, the traditionally accepted extremes of gender.

She also brought a detached, frigid air to many of her lyrics. On ‘Regrets’ she plays a bloodless character listing the chilling powers available to her: “I’ve got a dangerous nature, and my fist collides with your furniture…I’ve got a razor blade smile…fifteen senses are on my palette…I’m an electric wire and I’m stuck inside your head.” After establishing a consistent lack of emotion, lyrically, the slightest hint of tenderness in her lyrics would be magnified tenfold.

It must be said–because it’s not mentioned very often–that much of the groundwork for Lennox’ success was laid by Grace Jones. In fact Jones’ vocal licks and delivery, her ruthless lyrical style and her arty experimentation with androgyny right down to the signature crew cut were clearly recycled by Lennox in the early years of Eurythmics. What Jones lacked was commercial hooks in the songs, and what was special about the Eurythmics was the starkness of the electronic backdrop that Dave Stewart provided, which in my view couldn’t have more perfectly showcased the warmth of the human voice.

Pan & Throw

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing, Mixing, Remixing, Singing on May 19, 2009

This blows my mind every time I listen to it:

What you’re listening for is a 16-bar section toward the end of ‘Luv Dancin’ by Underground Solution…circa 1991. Classic house music on the legendary Strictly Rhythm label. The main hook of the track is a female vocal sample from Loose Joints’ disco classic ‘Is It All Over My Face’. There is a version with a full female vocal as well. But there’s a male vocal snippet from the Better Days Remix of Carl Bean’s ‘I Was Born This Way’ weaved into the tapestry and in this part of the extended version the producer decides to riff on that sample for a minute before winding down and man it gets me every time.

It’s partly the sample itself. It’s got that gospel depth to it…he’s feeling that shit…and the way he ends his phrase, trailing down, to a gritty release…there’s tragedy there.

But there are also choices that the producer and/or mix engineer made: the sample pans left and right, sometimes it’s ‘dry’ (no effects), sometimes there’s a delay throw (certain syllables echo) and sometimes there’s a reverb throw (a big roomy sound on it). The patterns entrance me. So simple, yet so complex. So inspired, so not systematic. I could loop those 16 bars all day.

Like A Needle In A ‘Reckerd’ Groove

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Singing on May 18, 2009

Further to the idea of micromanaging each syllable a singer utters, I want to point out that the natural way we pronounce words when we speak isn’t always the best way to pronounce them when we sing.

Why did Mick Jagger, and the great majority of all British rock’n’rollers from the get go, lose their limey accents and sound convincingly American when they opened their mouths to sing? It’s so common that a lot of us think it’s impossible to sing any other way. And yet Lily Allen retains every bit of her Britishness on record. It’s a choice.

And if a singer doesn’t make cool and pleasant choices–naturally or through trial and error–sometimes a producer helps them along.

In 2000 a young female R&B singer was signed to an American major label cutting her first album and a friend of mine was producing. One of the phrases in the chorus was ‘like a needle in a record groove’. In the girl’s natural speaking voice, she pronounced the word ‘recorrd’. Her sung pronunciation was more like the cooler and often-used ‘rekkid.’ But the producer asked her to sing ‘reckerd,’ because in the context of the song it the coolest choice: more retro, and therefore more current.

Don’t kid yourself…choices like this are made at the microphone every day. Whether the result is an honest representation of who the artist actually is, or more a persona the producer is designing, the identity of the artist on the final recording has to be likable! If the vocalist doesn’t make good choices naturally upon opening their mouth, the producer is left with no other choice but to instigate experimentation of this kind.