Archive for category Playing

Demoitis

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Playing, Production, Singing, Writing on April 11, 2013

Studioitis isn’t the only widespread malady in the world of recording. There’s also the much more serious demoitis.

Artists often make quick ‘demo’ versions of songs they’ll consider recording properly later on. In fact, during the making of an album dozens of versions of a song might circulate for the consideration of the creative team in the studio, and sometimes the business team at the label. The differences in the demos may be subtle: slight variations in volume levels, an altered word here and there, a few bars edited out. Or they may be sweeping: a new draft of the lyrics, a different tempo, drastically rethought instrumentation. But when a collaborator or an executive fights to retain elements they’ve become attached to in an earlier iteration of a track they are said to have a case of demoitis.

Debates follow. Often heated, sometimes explosive.

‘I just can’t get used to that new line in the second verse. It feels awkward to me.’

‘Cut those four extra bars before the bridge. The demo got right into it…I wouldn’t have changed that.’

‘This new tempo doesn’t give me the energy the demo had. What happens if we speed up the final mix digitally?’

Though experienced musicians often agree when something is ‘wrong’ with a song, music is ultimately a subjective thing. And it can be particularly difficult to maintain perspective on an ever-changing song you’ve heard played back a hundred times. How do you decide what goes out to the public?

First, try to hold back on presenting a song to the label or the artist’s management until it’s as close to finished as possible.

Making creative decisions by committee can leave a piece of music bloodless. Especially when the incubatory environment of the studio has been opened up for business executives to phone in some input from their offices. I’ve been involved in situations where two ‘final’ versions of a song were given to a room of A&R people at a label to vote on. In the end they asked for the two ideas to be merged, creating a frankensteined chorus that didn’t really preserve what was good about either version.

In my opinion, the Clive Davises and David Geffens of the world—music business executives who aren’t necessarily experienced in creative work but have a golden ear—are few and far between. (Ahmet Ertegun at Atlantic and Berry Gordy at Motown are examples of label presidents with an inside understanding of craft. They spent a good amount of time writing and producing themselves.) From what I’ve experienced, the majority of music executives are business-minded people with a love for music. While they will jump at the opportunity to participate in a creative decision, much of their input seems arbitrary. Suggestions seem to be lifted from trends or rules they’ve heard bandied about in the office.

‘How about a dubstep breakdown in the bridge?’ was popular this past year.

‘What about a filtered radio voice in the intro?’ was big with executives around the turn of the millenium.

I don’t want to fault execs for wanting in on the excitement of making music, but if it’s actually a situation of ‘I want to be able to tell people I suggested this [obvious, trendy] idea in a successful radio hit’ while at the same time being vague enough to claim no responsibility if the song flops…well that’s not helpful. Nine times out of ten the suggestion made becomes an awkward corporate mandate for some clashing parameter the studio peeps now have to work into the song. It’s not a solution; it’s just created more problem-solving work. As evidenced by the most successful labels and managers, who send a trusted producer and artist into the studio and have the wisdom not to open the door until the souffle rises, I think it’s better for all involved if executives use their creativity to come up with a kickass marketing plan instead. That’s something the artist likely can’t do, and the expert executive can take full credit for.

What about the decision-making that happens between the creatives behind that closed studio door?

Many times I’ve worked with a relatively green artist that wants to take demos home to get the input of their friends, family or significant other: input from people who aren’t necessarily creative but are either regarded as a Average Joes in the target market or a good barometer of whether the song is right for the person they know. I get it. Songwriting is new and mysterious, and on top of that you’ve been thrown into the studio with an opinionated person like me that you don’t know well enough yet to trust.

To be frank, it takes time to develop a sense of what’s working in the studio. When people have to go outside for input, it’s because they’re aware on some level that they don’t have enough experience to feel it when something—a line, a snare sound, a chorus vocal has squarely hit the mark. It’s a palpable feeling most experienced people in the room agree on when it happens. I started to recognize it after I’d been recording for about 6 years, and it took another few years to begin to know how to problem-solve things that weren’t giving me that ‘right’ feeling. (Don’t panic. Some people are faster at getting it than I was. And I make it my mission to help new artists get there ASAP.)

There’s a strong argument against doing a whole lot of market testing in lieu of relying on the gut instincts of a few professionals when you’re being creative. I’m gonna go all granola here and say that the origin of the song’s feelings and ideas is situated inside of the writers. I don’t see how polling others outside of the process can bring the song closer to its emotional center, and therefore closer to emotional impact for listeners.

The beauty of making music is that any new song you work with may have its own set of rules that generate a new approach. When you’re truly open to where a song wants to go, there are always new worlds to visit. No one person in the room has the answers, but if everyone drops their egos and taps in to what the song is dictating, a common direction usually emerges. In some cases of an extreme loss of perspective on the part of the makers, I think you can get an opinion about structural issues or the overall approach from another trusted professional who has their craft down.

Sometimes the demo does have something special about it.

For my solo work sometimes I like to write lyrics at the mic, changing words and lines until the puzzle pieces come together. And I usually feel the most effective vocal deliveries are the takes I record while I’m writing, moments after I’ve come up with the words I’m about to sing. That’s because I’m usually writing about something that’s going on with me at that time, and there can be an honest moment of catharsis or discovery in that first take. I’m not averse to re-approaching the vocal later on to try different things, but almost inevitably I end up with final vocal tracks made up mostly of my ‘discovery’ takes. One great thing about modern recording technology is when I’m co-writing with an artist I can get proper recordings of everything we come up with, using the same microphone as we go. This is like shooting a documentary film, trying to capture something that’s happening now to the singer, or even just a moment of honesty as they recall something in their past with great clarity. You never know when you’ll capture lightning, and I think it’s valid to fight to preserve moments like these from a demo, tweezing out individual recorded lines and conforming them to a later version of the song if necessary.

Other times—usually with seasoned performers that possess both highly developed vocal control and an actor’s ability to inhabit a song—I’ve found that capturing a great performance is a two-step process toward the end. 1. Have them take it home and learn the finalized version of the lyrics. 2. Have them come back in and record it three or four times, more or less straight through, over a fully produced track. The disjointedness of recording line by line with this type of performer tends to break their flow. What they want is to hear the song roll for a while so they can get inside it again and access the emotions of what they’re singing. As a producer, this is more akin to letting an actor play their part in a fictional narrative film. They’re skilled at using the power and nuance of their voice to create an illusion that this is happening to them right now. In truth it might be something they wrote years ago, or a fictional situation someone else wrote about.

When it comes to choosing vocal takes—or guitar solos or drum tracks—it doesn’t really matter how you got there. Whichever take gives you a chill down your spine is the one to go with. Though another version may be sonically better, or tighter, or more lushly produced…I’ll always feel that the version to go with is the one that made me, the producer, feel something. That’s a distillation, ultimately, of a producer’s job.

Ahmet Ertegun, Atlantic, Berry Gordy, Clive Davis, David Geffen, Motown

Sound Of The Funky Drummer

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Mixing, Playing, Production, Publishing on November 18, 2009

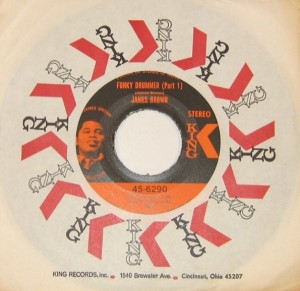

1. At a 1969 recording session drummer Clyde Stubblefield played a beat on a James Brown song that came to be called ‘Funky Drummer’.

The beat was so in-the-pocket that in the middle of the song Brown asks the rest of the band to lay back and give Stubblefield an 8-bar drum break to really sink into the groove.

The track was released, split in half, on two sides of a 7″ single in 1970 but was never included on an album.

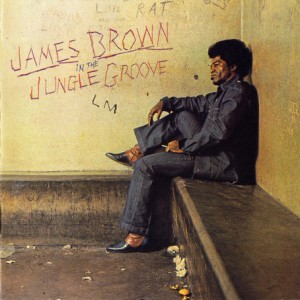

2. Some James Brown rarities and remixes were culled together in 1986 and released on a compilation called ‘In The Jungle Groove’. For the first time ‘Funky Drummer’ was available in its uninterrupted form, clocking in at 9:15.

The compilation also included a 3-minute Funky Drummer ‘Bonus Beat Reprise’ put together by New York DJ Danny Krivit which was essentially the cleanest and deepest bar of Stubblefield’s solo jam looped relentlessly, peppered only with the occasional guitar jab or James Brown vocal grunt to mark time.

3. Producers the world over knew what this Krivit re-edit was for.

Aside from a critical mass of rappers including Biz Markie, Big Daddy Kane, Ice T, Ice Cube and De La Soul jumping on the loop as the basis of new tracks, it began showing up as a rhythmic grid laid over pop songs far and wide. From 1988-1990 in particular it was an undeniable bastion of street cred for artists, and it is thought to be the most-sampled recording in history.

Fine Young Cannibals were among the first to arrive on the scene with the sweeping ‘I’m Not The Man I Used To Be’ from ‘The Raw And The Cooked’, lightly funkified with muted guitar riffs weaved into a sped-up Stubblefield groove.

Sinead O’Connor’s ‘I Am Stretched On Your Grave,’ from her seminal ‘I Do Not Want What I Haven’t Got’, LP was unapologetic about its use. Bottom-heavy and slightly slowed, the loop was upfront, holding the track down under O’Connor’s acapella vocal for over a minute before synth bass and eventually a celtic violin riff are introduced.

Some of the other best-known upfront overlays of the beat from that period include ‘Mama Said Knock You Out’ and ‘The Boomin’ System’ by LL Cool J, as well as ‘Freedom 90’ and ‘Waiting For That Day’ by George Michael.

4. Although the loop became fused with the aesthetic of its golden period, it hasn’t gone bad. The straight-up funk of it is impossible to deny, so it has continued to appear in a steady trickle, the producers dealing with its oversaturation in various ways.

Perhaps wanting in on the action while still recognizing its burgeoning overuse, the Beastie Boys threw in one dirty bar of the loop at the end of ‘Shadrach’. On 1993’s ‘Reachin’ (A New Refutation Of Time And Space)’ Digable Planets tastefully reinvented it by chopping it up and weaving it subtley into the jazzy beats of ‘Where I’m From’ and ‘Swoon Units’.

Japan’s Pizzicato Five did some crafty cut-and-paste on ‘Baby Love Child’ by laying the loop over an interpolation of the chords of the Righteous Brother’s ‘You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling’. (If the song title is meant to be a mash-up of ‘Baby Love’ and ‘Love Child’ by the Supremes, we really have a mutt of a track here.)

Genre-defying artist K-Os brought the loop full circle on 2004’s excellent ‘Joyful Rebellion’ LP by putting an aggressively distorted Funky Drummer upfront again on ‘B-Boy Stance’–as if to credit it, at least partially, as the roots of his rap attachment.

The only other drum loop that may approach the ubiquity of the Funky Drummer is the drum break on ‘Amen Brother’ by The Winstons. Virtually responsible for the entire genre of music known as Drum & Bass (or Jungle) the aural etymology of the sample, from inconspicuous b-side break to 24-hour assault on Drum & Bass internet radio stations, is tracked brilliantly in this video by Nate Harrison.

So…what about Clyde? The most-sampled man in history is in need of a liver transplant, but his musician friends have had to rally to raise the funds for him.

Since James Brown regularly taught his band the songs in his head part by part, it’s unclear whether Brown or Stubblefield came up with this beat. But because rhythmic contributions to music are not considered copyrightable ‘intellectual property’ in the same way melody and lyrics are, Stubblefield would not have been credited as a writer on the song either way. As such, beyond the original session fee, he wasn’t entitled to further royalties.

This lack of respect, at least legally, for rhythmic innovation is probably rooted in the fact that the system of notating chords and melody developed centuries ago in Europe is not equipped to capture rhythmic ‘feel.’ Because a drum beat lacks melody, it’s not considered unique enough to copyright. It’s interesting to note, then, that over the past 30 years popular music has become more and more dominated by rap, with hooks that are gradually becoming more rhythmic…we actually value melody less than we used to.

It’s also interesting to see that the unstoppable appropriation of audio and video in our new digital world has given rise to new fair-use philosophies such as that of Creative Commons licensing. Some people believe that a degree of freedom with intellectual property creates a healthy creative climate.

Still, in recent years the American Federation Of Musicians has developed something called ‘Neighbouring Rights’ in a bid to channel royalties to the individual players on recordings. Had this system existed at the time the Funky Drummer was laid down on tape, Clyde Stubblefield might have been up there on the Forbes list.

Amen Brother, B-Boy Stance, Baby Love, Baby Love Child, Beastie Boys, Big Daddy Kane, Biz Markie, Clyde Stubblefield, Creative Commons, Danny Krivit, De La Soul, Digable Planets, Fine Young Cannibals, freedom 90, Funky Drummer, george michael, I Am Stretched On Your Grave, I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got, I'm Not The Man I Used To Be, Ice Cube, Ice T, In The Jungle Groove, Intellectual Property, James Brown, Joyful Rebellion, K-Os, Listen Without Prejudice Volume 1, LL Cool J, Love Child, Mama Said Knock You Out, Neighboring Rights, Neighbouring Rights, Paul's Boutique, Pizzicato Five, Reachin' (A New Refutation Of Time And Space), Shadrach, Sinead O'Connor, Swoon Units, The Boomin' System, The Raw And The Cooked, The Righteous Brothers, The Supremes, The Winstons, This Year's Girl, Waiting For That Day, Where I'm From, You've Lost That Lovin' Feeling

The Polaris Music Prize

Have you noticed in recent years that Beyoncé and Alicia Keys have performed on every major American awards show? As much as I respect Ms. Keys (and am not particularly offended by Beyoncé) the only way I can explain their awards-show ubiquity over, say, The Roots, is that they’ve made it into The Club…an elite club of ‘artists chosen to be promoted by the majors’.

Widely accepted as the institutions that bestow the highest honours in music, England has the Brit Awards, America has the Grammys and Canada has the Junos. As viewers we watch thinking that we’re seeing musicianship rewarded…yet it always feels curiously like we’re seeing advertisements for pop albums we are expected to buy.

But last week I attended a refreshing and inspirational night here in Toronto: the Polaris Music Prize gala. There’s been an alternate reality taking shape in the world of music awards: since 1992 the UK has had the Mercury Prize, since 2001 the USA has had the Shortlist Music Prize and since 2006 here in Canada we’ve had Polaris.

All three Prizes are similar: the award goes to the band responsible for the best album released that year. Not the album that sold the most copies, but the best album…determined via large numbers of music critics submitting lists and/or voting. For the American Short List prize, nominees’ albums must not have reached Gold sales status (500,000 copies).

The Polaris winner gets a $20,000 cash prize, often used by the band to fund their next endeavor. This year’s ‘long list’ of 40 nominees included veteran folkster Leonard Cohen and newly-indie rapper K-Os. The narrowed shortlist of 10 bands performed live at the gala, simulcast on MuchMusic and CBC radio. CBC host Jian Ghomeshi was one of ten Canadian luminaries that each introduced a nominee, waxing personal about how the album affected them.

At one point a food-fight broke out between the tables of the obvious forerunners: celebrated new wave band Metric, Somalian-born rapper K’Naan and esoteric rock band Patrick Watson–who won the audience over by performing as a marching band weaving through the audience, wearing backpacks that sprouted bouquets of lights over their heads, the singer manipulating his vocal with effect pedals hanging from his neck, the rest of them handing out cookie sheets and wooden spoons for the audience to bang together as a room-wide rhythm section.

Newfoundland’s Hey Rosetta! stunned the audience with a performance that came in like a lamb and out like a lion, featuring a huge ensemble of supporting musicians crafting a painstaking climax around singer Tim Baker’s unmistakeable voice. The surprise of the evening came at the end, however, when hardcore punk band Fucked Up took the stage as the final performers and then walked away with the prize. Indeed, we’re looking at an unbiased jury process here!

I was shocked at the sheer amount of talent laid out before us that night. I was exceedingly proud to be doing music in Canada, which the world has begun to recognize is a disproportionate exporter of great music. Ask me if I cared about the Grammys after that…?

Alicia Keys, Beyoncé, Brit Awards, Grammy Awards, Hey Rosetta!, Jian Ghomeshi, Juno Awards, K'Naan, K-Os, Leonard Cohen, Mercury Prize, Metric, Patrick Watson, Polaris Music Prize, Short List, The Roots

I’m Only Inhuman: Vocal Trickery Through The Ages

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Creative, Engineering, Playing, Production, Remixing, Singing on September 6, 2009

Not content to replace pianos with synthesizers and drum kits with drum machines, producers have spent the last few decades pushing against that final frontier: the mechanization of the human voice. How have we dehumanized ourselves? Let me count the ways.

1. The Vocoder

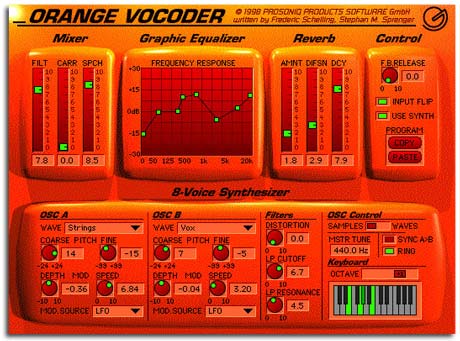

In the mid-70s ‘robot voice’ tracks began turning up in earnest. Kraftwerk was at the forefront with the Vocoder (not the Vocorder, as it is so often mispronounced, but the Vocoder: it is a ‘coder’ of ‘vocals’). For many years the Korg Vocoder was the standard unit, but all vocoders work on the same principle: you sing into a mic and the electric signal created by your voice shapes the sound coming out of the synthesizer.

One of the first commercial hits with a female robot vocal upfront was ‘Funkytown’ by Lipps Inc., in 1980. In 1983 Styx gave us ‘Mr. Roboto’.

In recent years software plugins like the Orange Vocoder have appeared, eliminating the need for another physical keyboard taking up space in the studio. The sound is a little less cutting–as the raw, aggressive squelch of old analog vocoders are still somewhat outside the realm of the computer–but tracks like 2002’s ‘Remind Me’ by Röyksopp have carved out a different niche for the software vocoder’s silkier sound. Korg’s MicroKorg keyboard and Ensoniq’s rackmount DP-4 have kept hardware vocoders alive.

2. The Talkbox

Stevie Wonder began using a talkbox in the early 70s, but after Parliament-Funkadelic alumnus Roger Troutman mastered the physically challenging device and formed funk band Zapp, radio got a steady stream of funk/R&B hits through the first half of the 80s.

A talkbox setup is in many ways the reverse of a vocoder. A synthesizer–typically a Yamaha DX100–set to produce a very strong, pure tone is plugged into the talkbox. A speaker driver inside the talkbox pumps the focussed sound out through a hose which is inserted into the corner of a singer’s mouth. As the singer forms words, their mouth physically shapes the sound from the synthesizer. This happens in front of a mic, which picks up the shaped synth sound coming out of the player’s mouth.

Roger Troutman’s command of the instrument shines on ‘I Wanna Be Your Man’.

For a visual demonstration, check out the great Stevie Wonder covering ‘(They Long To Be) Close To You’.

3. Retriggering

Evolving through the 80s, samplers like the Synclavier, Fairlight and Ensoniq Mirage were initially intended to realistically recreate acoustic instruments. The Emulator seemed to encourage more creative sampling however, and the Emu SP1200 was the sample-based drum machine that spawned the dopest hip hop beats. But by the late 80s the Akai S1000 was the rackmount sampler of choice, and the fact that you could expand the memory to load entire vocal tracks into it made retriggered vocal riffs the next logical step in house music.

In 1989 Black Box sampled parts of Loleatta Holloway’s vocal on 1980 disco hit ‘Love Sensation,’ placing it over new piano chords and a housebeat. The rhythmic retriggering of her impassioned vocal–the computerized sonic repetition of those growling phrases of sound–brought a clean, futuristic sensibility to dance music, an effect akin to referencing ‘Love Sensation’ in quotations. However at first those quotations were used without the appropriate footnotes…so court cases followed.

4. Stuttering

Through the early 90s house producer MK (Marc Kinchen) ran with vocal sampling, taking the retriggering concept to extremes.

Four examples of his work follow. On his remix of the B-52s’ ‘Tell It Like It T-I-Is’ he experimented with stuttering the last syllable of individual lines. This became a common technique borrowed by many producers, so MK forged further, finding a more individualistic practice: he began pulling single syllables from various places in the vocal track, reordering them to create hooky melodies (with nonsensical words). His 1993 remix of the Nightcrawlers’ ‘Push The Feeling On’ made massive waves, superseding the original version of the song without using a single intact vocal line. In demand as a remixer, he created hooky vocal stutters for the Pet Shop Boys on his remix of ‘Can You Forgive Her’ and for Blondie on his updated remix of ‘Heart Of Glass’, dropping the full vocal in between stuttered sections…and reportedly turning out one remix per week at $15-20K.

5. Timestretching

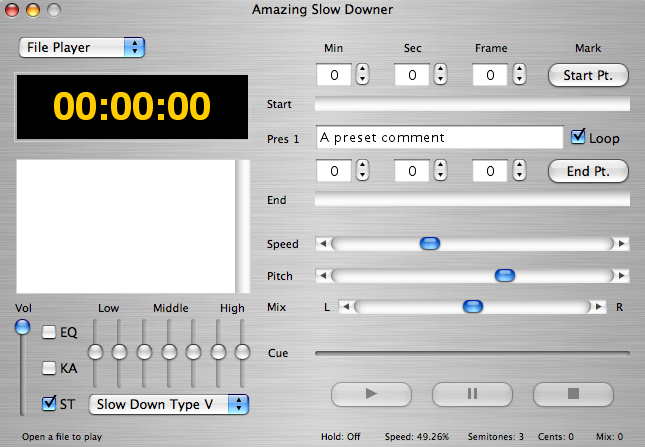

In the mid-90s Armand Van Helden took the baton, building a brand in part on the innovation of cheeky vocal processing techniques. ‘Timestretching’ audio using software plugins is a commonplace practice now, to make beats match in tempo or to conform an acapella to the desired speed of a remix. At the time, Armand Van Helden pushed the relatively new technology to the limit, placing ridiculously elongated vocal lines in the climaxes and dropouts of his tracks as dancefloor payoffs.

A few examples of this new intersection of the machine and the biological: he stretches the line ‘Sugar Daddy’ as a re-entry to the beat in his remix of CJ Bolland’s ‘Sugar Is Sweeter’; he stretches the hook vocal to prepare us for a drop out of the beat in his own track ‘The Ultrafunkula’ (the same track also exists as ‘The Funk Phenomena’); and finally during a dropout in his remix of Janet Jackson’s ‘Got Til It’s Gone’ he obsessively retriggers the sample of Joni Mitchell singing ‘don’t it always seem to go…’ (from ‘Big Yellow Taxi’), building to an unidentifiable, impossibly timestretched spoken line before dropping the beat.

All samplers and audio production software have a timestretch function, but it sounds like he used an early version of the ‘Amazing Slow Downer’ Mac program. Either that, or the application was conceived later specifically to achieve that Armand Van Helden sound.

6. Auto-Tune

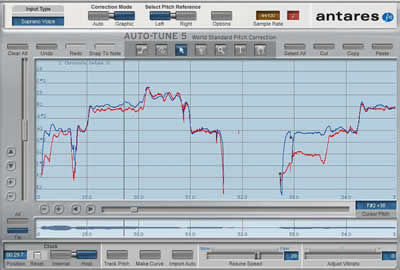

In 1997 a company named Antares marketed a rackmount box that could automatically correct a singer’s pitch in real-time. Shortly afterward, they released a software plug-in that did the same thing but also allowed graphical re-drawing of the pitch of individual notes in a recording.

Strangely perfect-sounding vocals began to appear on pop, country and R&B recordings, like the silky layers of Brandy’s voice on ‘Almost Doesn’t Count’ and ‘Angel In Disguise’ from her 1998 album ‘Never Say Never’:

Applied subtley the processing isn’t obvious, but the singer’s voice does take on an otherworldly pitch-perfection that we’ve all now come to expect. Singers, producers and engineers now assume that one of the phases of recording will be tuning the vocals.

7. Abused Auto-Tune

Put auto-tune into overdrive and you get what became known as the ‘Cher Effect’. In an interview in Sound-On-Sound producers Mark Taylor and Brian Rawling attributed the ear-twisting effect they applied to Cher’s vocals on 1998’s ‘Believe’ to a complicated vocoder setup. But what was obvious to most producers was exposed soon afterward: this was an auto-tune plug-in set to ruthlessly round the note up or down, causing lightning fast, perfect-pitch trills in the vocal. Madonna producer Mirwais took things a step further on tracks like ‘Impressive Instant’, redrawing the pitches of notes to create impossible, unexpected jumps in the melody.

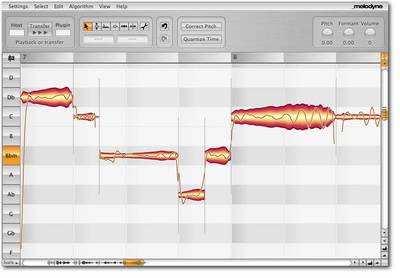

8. Melodyne

In recent years hip hop hook singers like T-Pain, Lil Wayne, Akon and Kanye West have recorded exclusively with an effect universally referred to as auto-tune. I’m convinced however that these guys are mostly using a newer program called Melodyne. It works in a similar fashion but allows much more precise editing of multiple layers of vocals, as well as control over an additional attribute of the performance: the tonal quality of a singer’s voice–from munchkin to giant– independent of the pitch.

Kanye West’s vocal on ‘Heartless’ and T-Pain’s vocal on ‘Chopped And Screwed’ (a song whose subject incorporates reverence to vocal trickery) demonstrate the metallic sound of multiple takes of the lead vocal processed through Melodyne. On 2009 single ‘D.O.A. (Death Of Autotune)’ rapper Jay-Z started a backlash against the generic use of tuning as a crutch for singers.

Celemony, the makers of Melodyne, will soon be releasing a new version that will be able to isolate and manipulate the pitch of each note within chords on recordings (as opposed to individual notes). It’s anybody’s guess where this will take producers next in the field of vocal cybernetics.

9. Digitech Vocalist

For some reason Digitech is not one of the major go-to companies when it comes to effects boxes, but they’ve always pushed the envelope of digital processing. Imogen Heap’s 2005 hit offering ‘Hide And Seek’ was entirely acapella-and-effects, bringing a fresh ear-bending sound that could have been a traditional vocoder but for the oddly futuristic slides between notes. The lush, fanned out harmonies were created from single vocal tracks by the Digitech Vocalist box, which is able to digitally extrapolate live harmonies on the spot based on chords played on guitar or keyboard.

Look for additions to this article as new vocal processing technologies are used and abused by producers.

(They Long To Be) Close To You, Akai, Akon, Almost Doesn't Count, Amazing Slow Downer, Angel In Disguise, Antares, Armand Van Helden, Auto-Tune, B-52s, Believe, Big Yellow Taxi, Black Box, Blondie, Brandy, Brian Rawling, Can You Forgive Her, Cher, Chopped And Screwed, CJ Bolland, D.O.A., Death Of Autotune, Emu SP1200, Emulator, Ensoniq, Fairlight, Funkytown, Got Til It's Gone, Heart Of Glass, Heartless, Heil, Hide And Seek, I Wanna Be Your Man, Imogen Heap, Impressive Instant, Janet Jackson, Jay-Z, Joni Mitchell, Kanye West, Korg, Lil Wayne, Lipps Inc., Loleatta Holloway, Love Sensation, Madonna, Marc Kinchen, Mark Taylor, Melodyne, Metro, Mirage, Mirwais, MK, Mr. Roboto, Never Say Never, Nightcrawlers, Parliament-Funkadelic, Pet Shop Boys, Push The Feeling On, Remind Me, Ride On Time, Roger Troutman, Röyksopp, S1000, Sound-On-Sound, Stevie Wonder, Styx, Sugar Is Sweeter, Synclavier, T-Pain, Talkbox, Tell It Like It T-I-Is, The Funk Phenomena, Timestretching, Ultrafunkula, Vocoder, Yamaha, Zapp

Before The Music Dies

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Playing, Publishing, Radio, Singing, Writing on July 28, 2009

Hot documentary alert: I just saw a 2006 film discussing the changes in the structure of the music business that have led us to where we are now.

Erykah Badu, Bonnie Raitt, ?uestlove, Eric Clapton and Branford Marsalis chime in, describing the frightening effects of changes to radio station ownership laws, the practice of song testing and the merging of hundreds of record labels into four majors. The film’s directors, Andrew Shapter and Joel Rasmussen, demonstrate how a songwriter, producer and video director can manufacture a pop artist out of a young female model with virtually no musical talent.

Definitely worth watching, though the filmmakers seem to have a strong bias in favour of retro blues-based music.

Watch the trailer here. Download the film here. Thanks to Steve and Chris for passing it along.

?uestlove, Bonnie Raitt, Branford Marsalis, Eric Clapton, Erykah Badu

Precision Performance

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Playing, Production on May 18, 2009

My instrument is the piano. However, despite (or as a result of?) many years of classical training, I do not consider myself a serious session player. When I’m recording, I play what I need to play in bits and I edit my performances until they are what I hear in my head.

But I want to show you an example of a precision player.

Guitarist James Bryan tours with Nelly Furtado. He’s also a writer-producer and a member of The Philosopher Kings, Prozzak and Sunshine State. James is one of Canada’s top session guitarists. I’ve been lucky enough to work with him on my own material and some songs I’ve produced for other artists.

He doesn’t own an endless array of guitars and effects…just the basics are necessary. But this guy shows up at a session and upon listening to the song once, he can pretty much ascertain exactly what needs to be done: which guitar(s), how many overdubs, what rhythms will be best. Give him the first chord and he can map out the rest of the chord changes in a minute or two. His feel and musical instincts are incredible.

What really sets him apart, though, is his precision. This is someone who began playing his instrument obsessively as a small child and never gave up practicing. Each strum is effortlessly controlled in rhythm, velocity and expression. He often needs only one take; two takes at most for a particularly difficult passage.

Here’s an example of that precision: stereo acoustic rhythm guitars he recorded on a song for me. (I’ve muted everything but the drum track and his two acoustic guitars.)

No editing necessary: his performance is perfectly even on both sides. He’s a joy to work with. If you want to be a live touring musician or session player, aim for this degree of precision.

-

You are currently browsing the archives for the Playing category.

-

-

Archives

- April 2013 (1)

- August 2011 (1)

- November 2010 (1)

- August 2010 (3)

- July 2010 (1)

- March 2010 (1)

- January 2010 (1)

- November 2009 (1)

- October 2009 (2)

- September 2009 (1)

- August 2009 (1)

- July 2009 (4)

- June 2009 (7)

- May 2009 (10)

-

Meta