Song Structure 101

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Writing on June 14, 2009

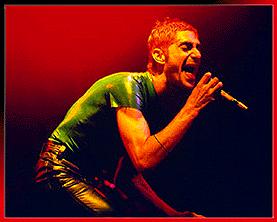

Legend has it that Jane’s Addiction frontman Perry Farrell came up with ‘Been Caught Stealing’ specifically to prove he was capable of–though not particularly interested in–writing radio hits. Of course after the song spent four weeks at #1 and the band made the jump from college dorm buzz to a household name, Farrell had the resources to create Lollapalooza and retire back to writing whatever he felt like writing.

Formulaic writing gets a bad rap. Nobody wants to feel that the music they love was written in a calculated way, but I think it’s important to draw a distinction between upholding the tradition of the 3-minute pop song and completely reverse-engineering music based on market studies. The fact is, for better or worse, every one of us has been programmed to understand a couple of basic song structures.

The main one: Verse–Prechorus–Chorus–Verse–Prechorus–Chorus–Bridge–Chorus

Sometimes there’s a short intro. We expect the first verse to spell out what the song is going to be about. The prechorus that follows builds tension toward an anticipated payoff. The chorus is the catchy main idea that we’ve been waiting for–the repeated part that everyone can sing along to–and it usually contains the song title. (In olden times it was known as the ‘refrain’, and it’s more and more often referred to as the ‘hook’ in the age of hip hop.)

In the second verse the story continues to be told. Expect a new idea or a new perspective to be introduced, just when it might start getting boring. Lyrics are almost never repeated in verses. The prechorus that follows may contain the same words as the first, but it may be shortened to get to the second chorus faster. Next, three quarters of the way through the song, a bridge (or ‘b-section’) breaks the melodic pattern…it’s somewhere else to go for a moment. Sometimes solos are used in place of, or in addition to, bridges. Finally, we’re taken home with the biggest chorus yet at the end.

Occasionally you’ll get a song with no prechoruses, or one with an outro or ‘tag’ at the end. But this basic structure applies to virtually every song you’ve ever heard. Even long club mixes are the same: there’s just a longer intro, a longer bridge in the form of a drum break or build, and a longer outro.

Many new writers are unaware of this structure, or they will intentionally start writing without studying it with the belief that this will allow them to express themselves in a pure way, unfettered by convention. However it’s basically inevitable that when they do hit on a structure that feels right, it will be because they’ve kept moving parts around until they have something that follows the structure described above.

So it’s just faster to accept that this song arc is part of a language we’ve all learned subconsciously. It’s a tradition. There is still plenty of room within that tradition to be an individual. In many ways we should be thankful that the structure pins down a couple of constants for us. What sets writers apart is the substance they fill this pre-determined form with. And the more experienced writers will naturally begin to manipulate the structure in ways that make sense to all of us as listeners.

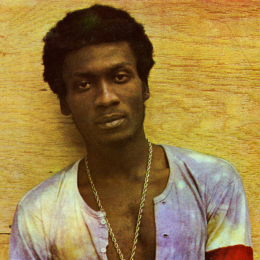

The other song structure worth mentioning is an older form that has its roots in gospel hymns: Chorus–Bridge–Chorus–Bridge–Chorus. Jimmy Cliff made use of its spiritual feel in his classic ‘Many Rivers To Cross’:

Each chorus begins with the lyric ‘Many rivers to cross,’ and from there he identifies another aspect of his tribulations: ‘…and it’s only my will that keeps me alive. I’ve been licked, washed up for years, and I merely survive because of my pride.’ The bridge section, which appears twice to provide a respite from the chorus, addresses his loneliness: ‘But loneliness won’t leave me alone. It’s such a drag to be on your own. My woman left and she didn’t say why. Well I guess I have to cry.’

One of the few songs in the history of pop music that defies convention is Marvin Gaye’s classic ‘Let’s Get It On’. The song does follow Chorus-Bridge-Chorus-Bridge-Chorus form, but the melody is ‘through-written,’ meaning each section takes a new melodic route, with very little repetition. It’s extremely difficult to write something that stays hooky throughout without ever repeating the melody…but if you think you know as much as Marvin Gaye knew about writing when he came up with the seemingly effortless ‘Let’s Get It On’, I encourage you to try it!

To Sign Or Not To Sign

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Publishing, Radio on June 11, 2009

In 2000 Courtney Love made a speech at a music conference. She got out her calculator and demonstrated what happens when a band signs a dream deal with a major label and has a hit album: the label makes an average of $6.6 million and the band makes an average of $0. The way things are structured in those deals, all of the costs of recording and promoting an album are passed back to the artist, and unless the band has multiple hit albums in a row they don’t actually make money.

This is not to say that the band isn’t living a suitably Hollywood lifestyle–touring and enjoying the trimmings of success–or that they might not benefit in the long run from having their identity erected to ‘household name’ status above the deafening din of all of the other aspiring musicians in the world. The major labels have built networks of promotional resources around themselves precisely for that purpose.

However, almost ten years after Love’s math class, the sea change in the music industry has lumbered forward. File sharing has won: physical product and the ‘brick-and-mortar’ stores that stock it are no longer necessary. All the filler labels used to cram onto CD-length albums is systematically ignored now that legal and illegal digital downloads are the norm. The majors have eaten up the rosters of even more independent boutique labels, destroying the influence of some of the innovative thinkers of those startups in an attempt to eliminate street-level competition. Sony and BMG merged, bringing the major label count down to four…that is, four clumsy multinational giants plagued with red tape and corporate approval hierarchies in a business that is utterly out of touch with ‘what the kids want’ because gut-level instincts have given way to copycat marketing models.

Essentially, it’s become common knowledge among insiders that for the foreseeable future, the major labels are going to be good for one type of music: music mass-marketed to 11-year old American or British girls. The artists doing that kind of music are often primarily concerned with fame, so they’re not thinking much about the money, assuming it will follow. They will rarely make a cut of the most potentially lucrative income source–writing royalties–because the labels will bring in professional writers who will come up with commercially viable material…or at least material that the radio stations will throw their support behind when they see writers with a track record of radio hits in the credits.

The labels all have sister companies in the music publishing world (Sony has Sony ATV Publishing; Warner has Warner-Chappell Publishing; EMI has EMI Music Publishing) that represent hit-making writers, and the cut those companies make gets routed back into the machine. It is true that often, however, the artist’s manager will insist that their non-writing artist come up with a line or two in a verse so that they’ll be cut in to the royalties at least in a minor way…and with their name in those credits, they’ll be perceived by fans as a singer-songwriter. (And this eventually leads to non-writing artists being offered lucrative publishing contracts, if their records are selling well.)

If you’re doing music aimed at anyone other than tweens, it’s probably a safer bet to stay indie, own everything and work hard to cultivate a solid grassroots fanbase. At this point in time, the majors are hemorrhaging money, so they expect artists with loftier musical ambitions to have done their own ‘artist development’…ie come up with their own image and styling; work out the details of their stage show; write some hit songs and grow an audience. So, ironically, if you do find yourself in the middle of a bidding war between the majors you may realize there’s not much more they can do for you. You might as well keep 100% of your profits rather than turn over 50-90% of your profits to somebody who didn’t show their support by investing in your potential earlier on.

There is no one ‘evil person’ at the helm of all of this financial deception. Artists are often focused on making their music and consider themselves not particularly business-minded, so they ignore the work they need to do to educate themselves.

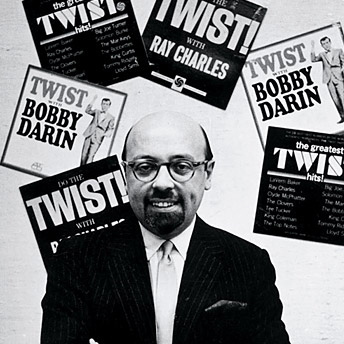

Many execs at labels and publishing companies are failed artists, or people who dreamed of being artists but never believed in themselves enough to give it a real shot. They want to stay involved in the industry, for the love of music or the cool factor, but how many execs could possibly have the instincts of industry legends like Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun, a man whose understanding and raw passion for music led him to build a diverse stable of equally legendary artists?

These days there are so many jobs on the line in these multinational record companies, risk-taking of any kind has consequences…hence the constant references to existing successes: ‘make a track like Bleeding Love by Leona Lewis.’ And the writers and producers all scamper off to study how the reference song is constructed, coming back with paler and paler imitations; further and further from what a hit song is supposed to be: an epiphany.

It’s a simple fact of the economy that growing a band on a global scale over a series of albums is now financially impossible. So, as Howard Jones would say, no one is to blame. I suppose you could waste your time blaming the forward march of technology, specifically mp3 compression and high-speed internet, the way the advent of sampling was once demonized. But industry guru Bob Lefsetz, for example, trumpets on a daily basis in his blog that the majors are on their last legs because they constantly miss the boat by fighting technology rather than finding ways to capitalize on it. He also repeats relentlessly: be a good, original musician; write good, original songs; do it because you love it and not because you’re looking to get rich. In other words, Build It And They Will Come.

I think most musicians commit to their vocation at an early age with the erroneous belief that a good song by someone with a great voice becomes a hit because everybody in the industry goes out of their way to make it so in the name of sharing exceptional new music. Most music fans who are industry outsiders exist their whole lives believing that this is so. They may have heard that the entertainment industry is full of sharks, or that it’s a hustle, but people rarely hear concrete explanations of shady practices.

A few things to think about when considering signing with a label, publishing company or manager:

– Most radio stations are corporate entities now, often with multinational parent companies, and they have strict ‘formats’ detailing specific parameters (style, length, song structure) for what they play. The major labels have departments that feed the stations with material, and the stations trust the labels to bring content their listeners will be excited about. If you go the indie route, expect to pay an independent radio promoter several thousand dollars per month, per song, to try to get your material played on a specific format. The success rate for the investment is lower than if you are with a label. Material rarely gets in the door without a promoter. Whether radio is important anymore, with YouTube promoting most music, is another discussion entirely.

– If you do not live in the country where the head office of the label or publishing company you’re interested in is located, you will be trying to attract the attention of executives who have limited power over their artists’ destinies. In other words, if you sign with EMI in any country other than the UK or you sign with Universal, Warner or Sony in any country other than the US, your music will never be released in other countries unless the head offices there can be persuaded to back you as well. Writers signed to the offices of major publishing companies in countries other than the US or UK have their material pitched for use in movies, television and ads after domestic writers’ material is pitched as the head office stands to make less of a cut on foreign writers’ material.

– It’s critical to get the right fit: if you sign to the biggest label or publishing company because of their clout, and the individuals working at that office are not particularly excited about your music, you may find your project constantly blocked or shelved. Then it’s a waiting game to be released from your contract so your career can move forward. It’s also not unheard of for labels to sign artists with no intention of putting out their music…rather, the goal was to eliminate competition in the genre of one of the company’s existing artists.

– The same goes for managers. If you sign to the most powerful manager in your city–paying them 20% of your income for a period of years–make sure that they’re interested enough in your career that you are a priority for them. If that manager has another artist that blows up worldwide, you may find your needs ignored. It’s often better to be self-managed than managed by the wrong person.

– Because of their unique position negotiating contracts between parties in the industry, music lawyers know most of the players…be they labels, managers, publishers, producers, artists or writers. Often lawyers will help people network with each other, but watch out for biases and vested interests.

– Owning all of your publishing on a hit song can be very lucrative, however owning 100% of a song that isn’t being pushed to the right artists or advertisers is owning one hundred percent of nothing. The right publisher can help you make a living by pitching your material and setting up writing opportunities with artists. However if a television series is looking to use one of your songs, for example, they must clear its use with all parties who own a share. The more parties involved and the bigger the publishers, the more red tape…making it too much of a hassle for some agencies to bother with.

Breakin’ Dishes: Capturing Sound Not So Perfectly

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production on June 7, 2009

When somebody drops a glass or breaks a plate in the apartment next door, you know it’s happening for real–and not in a surround-sound movie they’re watching–because what we can capture on disc is still slightly lower quality than real life sound.

Since the first recordings made on cylinders in the late 1800s we’ve always pressed forward, unquestioningly, in our efforts to close the gap between ‘live and memorex’. Technologists, engineers and audiophiles have fought tirelessly to further extend the frequency range, dynamics and resolution of recordings. In the late 80s the jump to digital recording brought us infinitely closer to being able to reproduce sound without colouration of any kind, and science continues to improve upon the resolution of digital with the goal, I suppose, of having there be no discernable difference between real and reproduced sound.

This has been amazing for action movies. In some instances crisp, clear recordings with deep bass, pristine treble, wide spatial staging and infinite dynamic range should be the goal. But there is also a powerful group of mostly old-school music producers–the David Foster types, the Nashville types–that in my opinion have chosen to use the widescreen ‘colourless’ nature of digital to strip mainstream recordings of much of their character.

Looking back on pop culture over the last hundred years, some of what we hold dearest is that which we can’t quite ‘touch’…that which is partially obscured because it wasn’t captured realistically.

When we watch a black and white movie from the 1930s, a technicolor movie from the 1950s, or even a film shot on washed out Kodakchrome/Eastman stock from the 1970s, we’re losing ourselves in a world that is not quite our own…it’s a romanticized version of life brought to us in part due to a lack of honest colour information.

Similarly, when we listen to classic Motown, with its boxy sounding drums, distorted tambourines and general sonic blurriness, we’re transported to that sweaty basement in Detroit where players and singers delivered magic. And it’s not just nostalgic in retrospect. I maintain that it was already full of nostalgia when it first hit the radio precisely because it didn’t sound like real life: the very character of the sound stoked our collective imagination as to where this musical spirit was coming from.

If music is a window into other peoples’ real and imaginary worlds, why is there so often a de facto assumption that we even want it to sound true-to-life? And, once it’s possible to record sound at real-life resolutions, does that mean we’ll cease to experience decade-specific nostalgia as, moving forward, sound is always perfectly colourless?

I always tend to appreciate the planned or accidental limitation of sound quality, like a good pair of distressed jeans. I don’t feel that the most expensive microphone, the biggest mixing desk, or the greatest clarity and sonic detail should always be the goal. Capturing a moving performance should be first, and if a lower end microphone is all that was around when it happened, I don’t believe the artist should re-perform it on a $17k Neumann tube mic. In fact maybe a Fisher Price microphone should be plugged in now and again to see what will happen.

Some examples of intentionally and unintentionally ‘distressed’ recordings through the ages:

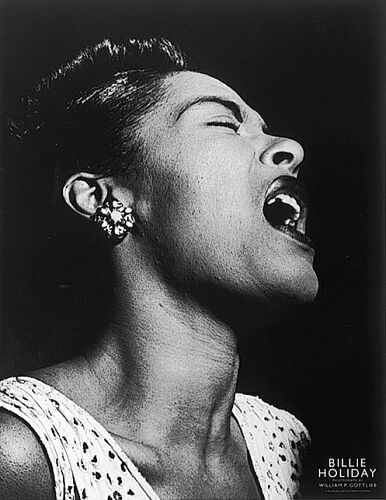

1. Billie Holiday’s 1935 recording ‘It’s Too Hot For Words’ was of course cut on a shellac disc using relatively primitive equipment. The dated style of the recording–the distortion and lack of bass and treble information–renders her forever untouchable, a tragic legend.

2. On ‘Strangers,’ the third track on Portishead’s 1994 groundbreaking debut disc ‘Dummy’, after a full frequency sonic barrage of an intro we plunge unexpectedly into what appears to be an improvised demo jam made on a handheld cassette recorder. Muted, distorted and noisy, Adrian Utley’s soulful jazz electric supports some of Beth Gibbons’ most shimmering vocal moments. This section of the song may in fact have been laboured over on high end recording equipment and then played back through a distorted guitar amp to achieve this effect…we may never know. By verse 2 we’re back in 1994 standards of high definition audio.

3. Throughout the 1990s layering vinyl surface noise over highly produced rap, R&B and pop was a common move to get back some of the nostalgia that seemed to be lacking on pristine digital recordings. 1996’s ‘No Love’ by Erykah Badu demonstrates the tactile feel of vinyl, as well as an intro section where the bass and treble are also filtered out of the music to make it sound lo-fi. When the track kicks in (and the filters are removed) note that the quality of the instruments is uncompromised by the vinyl pops we hear over top. This gave 1990s recordings a different feel than old recordings on actual damaged vinyl, because each click or pop on a record would actually distort the sound quality of the musical elements as it happened.

4. UK dubstep producer Burial puts down a bed of heavy, stuttering beats. On that he places a wax paper layer of lush, filmic ambient pads. Next, he sprinkles obscure mix-and-match R&B acapellas, filtering out the treble to create lyrical ambiguity. Finally he wraps the whole thing in a layer of sonic gauze using an expanded palette of crackle, ranging from standard vinyl crackle and tape hiss to rustling sounds and recordings of fire. The result, heard here on a drumless segue after ‘Shell Of Light’ on his 2008 album ‘Untrue’, is something like witnessing a merciful event through a frosted window.

These are all analog methods of bringing character to recordings: the limitations of vinyl, tape and guitar amps. But in the early part of this century we’ve seen some indication that producers will continue to time-stamp recordings by beginning to find useable limitations within the digital realm. For example, the glassy digitized sound of low quality mp3s has inspired some producers (most notably Mirwais, who produced Madonna’s ‘Music’ and ‘American Life’ albums…and of course Daft Punk) to apply similar lo-fi digital effects to vocals and music loops.

This type of experimentation gives me hope, in the digital age, that we won’t be listening to the silky smooth sound of David Foster muzak for the rest of eternity.

Total Deconstruction: Buffalo Stance

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Remixing, Writing on June 3, 2009

1. In 1982 the Sex Pistols’ manager Malcolm McLaren jumped ship on punk by traveling to New York and appropriating elements of cutting edge hip hop culture on a groundbreaking single called ‘Buffalo Gals’.

2. In 1986 a British duo Morgan McVey released a painfully cheesy pop song called ‘Looking Good Diving.’

3. The duo’s Cameron McVey asked his wife, Neneh Cherry, to come in and rap over an instrumental version of the song. That version was released as the b-side, listed as ‘Looking Good Diving With The Wild Bunch’. (She was a member of the Wild Bunch crew, along with members of Massive Attack.)

4. Oddly, Nick Kamen also recorded a version.

5. In 1988 Cherry’s rap was salvaged–along with the excellent synth hooks from Looking Good Diving–and parts of ‘Buffalo Gals’ were scratched in over a new beat to concoct Neneh Cherry’s seminal single ‘Buffalo Stance’.

6. The song was then remixed to death, in an era when remixing was taking a giant leap. The purpose of a remix had always been to extend a song, perhaps throwing in a little extra ear candy for the dancefloor. But now that you could load the whole acapella into a sampler and access sections of it at will–as opposed to having to run it off of a linear master tape–total deconstruction became the norm.

Dropping the needle on a single like ‘Buffalo Stance’, you heard every familiar nuance of the vocal track over an entirely unfamiliar backdrop…structure, chords and rhythms entirely re-imagined. It took three 12″ singles and one 7″ single to squeeze all the juice out of this track. It was as though the remixers tag-teamed, sampling elements of each others’ versions and riffing on them further.

Below are a series of excerpts: the classic benchmark ’12” Mix’ which was the long version of the original Tim Simenon production; the Dynamik Duo’s sparse ‘Sukka Mix’ containing all kinds of gritty vocal outtakes; Arthur Baker’s ‘1/2 Way 2 House Mix’ which placed the vocal over a mellow house-ish groove before moving on to an abstract collage of vocal samples; Kevin Saunderson’s crunchy ‘Technostance Remix I’ which sort of encapsulated samples of the original version in between dubby loops; and finally Massive Attack’s bizarre disco take entitled ‘There’s Nothing Wrong Sukka Mix’.

7. In 1990 George Michael got his fingers in the pudding by releasing a remix of ‘Freedom 90’ that combined vocals from his original song with his own rendition of Soul II Soul’s ‘Back To Life’. In re-singing it, he lovingly emulated Caron Wheeler’s every phrase. The mix also contained a sample of the fiddle riff from Sinead O’Connor’s ‘I Am Stretched On Your Grave’ and a re-created loop from ‘Buffalo Stance’ (the ‘Buffalo Gals’ scratches and his rip of Neneh Cherry’s ‘Get Funky’). This ‘remix’ (or medley, as it would more accurately be called, since he took this opportunity to sing portions of peoples’ songs) felt like a synchronistic experience for me as those particular songs he chose to combine had all been huge for me that year.

What fascinates me about this evolution is not just the multiple levels of cut-and-paste that went on through these productions, but the fact that this exposes a clear example of the sort of rewriting/rethinking that sometimes must happen before a song hits its apex. Cherry’s rap on the b-side of ‘Looking Good Diving’ isn’t the fully realized version of the lyrics she went with on ‘Buffalo Stance,’ and neither is her confidence in place, yet, vocally.

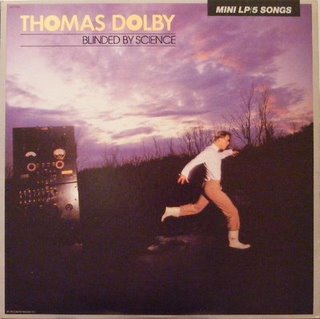

Having A Production Sound: Thomas Dolby

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production on June 1, 2009

As a kid in the early 80s when I heard brand new ear candy on the radio I waited for the 411 from the announcer at the end of the song, scraped together some coin, grabbed my bike from the garage and rushed to the record store to get that hot pressed wax in hand. Some of the most urgent bike rides occurred after hearing these songs:

In order, you’re listening to the haunting synth pad intro of Foreigner’s ‘Waiting For A Girl Like You’ followed by the rock-funk atmosphere of ‘Urgent’ (another single from the same album), then the new wave whip-cracking of ‘New Toy’ by Lene Lovich and finally the tight slab of synth-funk that is Thomas Dolby’s ‘She Blinded Me With Science’.

I like all kinds of music but something about synthetic textures, from classic Pink Floyd to current Electro, has always held extra-deep excitement. Checking the liner notes 20 years later I realized there was no coincidence that these songs pressed similar buttons for me: they were all touched by Thomas Dolby’s electronics.

For a moment in the early 80s Thomas Dolby exemplified the potential of modern synthesized pop. On one side he played keyboards and programmed drum machines for mainstream rock bands like Foreigner, on the other he was called in to write and produce for underground phenomena like Lene Lovich.

Born Thomas Robertson, he acquired the ‘Dolby’ nickname in high school when fellow students mocked his obsession with his tape recorder. (Dolby Laboratories later filed suit against him.) When it came time to launch his solo career, he sampled british mad professor television personality Magnus Pike for ‘She Blinded Me With Science’, and was then photographed running from an ancient mainframe computer in full science teacher garb for the cover of the ‘Blinded By Science’ EP. The debut album that followed was titled ‘The Golden Age Of Wireless,’ in reverence for the magic of early radio, vaccuum tubes and all. Even with his unabashed romanticization of all things geeky, however, he escaped total nerddom by maintaining an edgy new wave leaning at all times.

Dolby certainly had a clear identity–lyrically, vocally and imagewise–but what was most remarkable was the way he asserted his identity within his production sound. I don’t know what brands of synthesizers and drum machines he favoured, but the choices he made with his sounds were unmistakable. Keyboards were haunting and drums were at once synthetic and funk-infused. Not everything was electronic. Guitar, bass and real drums were weaved in tastefully. His output carved out a singular, stylized sonic niche…he achieved a goal every producer aspires to.

Chord Progressions: Making People Feel Something

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Writing on May 30, 2009

I always wince when industry execs refer to songs as being emotional…as in ‘let’s hear that first song you played again, the one with the emotional chorus.’ Correct me if I’m wrong, all music is supposed to make you feel something. But what they’re getting at is songs that become the biggest hit singles often have an extraordinarily strong emotional pull.

Melody and lyrics are critical when it comes to emotional pull (and in my opinion a talent for melody is the one thing that a person can’t be taught) but well-written chord progressions are key, and the importance of the series of chords chosen for a song is overlooked by many new writers.

Sitting down with the piano or guitar we often believe that whatever chord changes first came to mind are the foundation of the song; that it’s unchangeable and the task is now to write some words and melodies over top. However in truth you can manipulate the chords under a vocal just as readily as you can manipulate the melody: remixing often involves doing just that. When you stop automatically trusting whatever chords you happened to pick out of the air, you begin to have some control over how the song makes people feel. This is what people refer to as songwriting ‘craft’ and it’s part of getting professional about your writing.

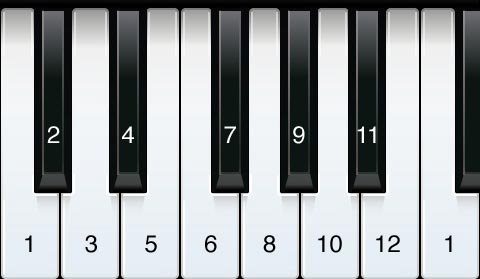

Without getting too far into the dry wasteland that is music theory, here’s a way to open up your writing.

If you sit at a piano and play chords up the scale of C Major, this is what you’ll get:

Position 1 = C major

Position 2 = D minor

Position 3 = E minor

Position 4 = F major

Position 5 = G major

Position 6 = A minor

Position 7 = B diminished

When most people begin writing, they’ll try something basic like alternating back and forth between two chords, say Position 1 (C major) and Position 4 (F major), and they’ll go with that as their verse or chorus. Simple progressions that sound good to our ears tend to become the standbys we go to unless we challenge ourselves. I’ve noticed that some people believe you can only move a step at a time in either direction…creating chord progressions like 1, 2, 3, 2. You can jump all over the place, and you should.

For years I was in the habit of only using the 7 chords readily available in the scale. Until I was shown, I didn’t realize that I could, for example, play a progression like 4 (F major), 5 (G major) and then a minor 5 (G minor, which is not naturally in the key of C) and then 1 (C major) without the earth caving in. In fact, go ahead and move to any chord from where you are. You can move from position 1 to position 4, but use an F Minor instead of an F Major. Or you can play a C Major followed immediately by a C Minor.

When you let go of the scale you’re in and allow yourself to see all 12 notes available on the keyboard you realize that at any given moment, from where you are, there are 23 other basic places that you can go. (The major and minor chords of all 12 notes, minus the chord you’re already on.) Sometime, when you’re sitting at your instrument with no inspiration, I recommend jumping around between chords for a while as a way of opening up your writing. Some of the jumps you’d normally never think to play can spark a feeling you know from other music, but didn’t know how to evoke yourself…and you can find yourself writing a song around the device you’ve just discovered.

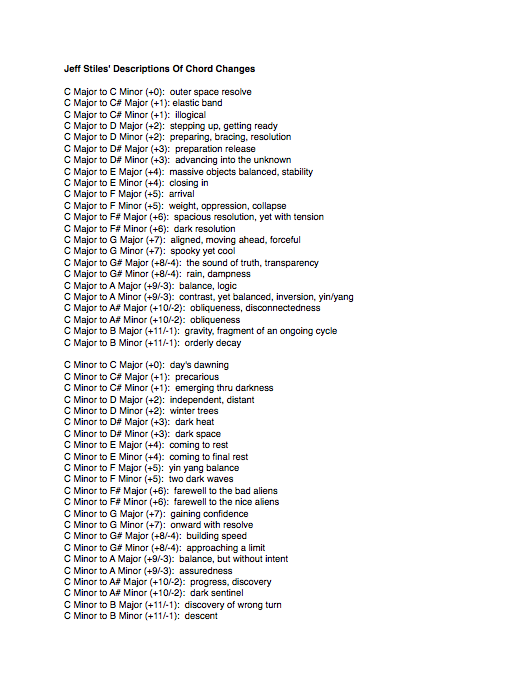

A few years ago I did an experiment with some friends who write. We all separately played C major followed by C minor…and then wrote down a description of how that chord change felt. Then we did C major followed by D major, and all of the other possible jumps moving up the keyboard.

Put side by side, many of our written descriptions described similar emotional responses. Some images that kept showing up were the feeling of ‘stepping up or down,’ (fairly obvious for standard incremental movements along the keyboard like C major to D major); ‘precarious balance’ (for less standard incremental movements like C minor to C sharp minor); ‘optimism’ or ‘pessimism,’ (when the chord change involved changing between a major and a minor); ‘assuredness’ (a common jump like C major to A minor); even ‘planetary’ feelings (for odd longer jumps like a C major to F-sharp minor, which are obviously used in lots of space movies).

So it looks to me like, either by nature or nurture, we feel chord progressions in similar ways. When you’re writing at your instrument and what you’ve got feels okay but not great, I encourage you to challenge one of your chord changes by trying the 22 remaining possibilities. If you do this often enough, you’ll develop a strong command of the emotions you bring as the listener moves through the song with you.

Hard Cuts, Beat Mixing & Train Wrecking: The DJ As Performer

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing on May 21, 2009

It’s difficult for an audience in a club to know exactly what the DJ is manipulating at a given time and what’s already part of the track they’re playing. Too often I’ve heard someone on their way out of a club crying ‘the way that DJ remixed the new Britney was fiiierth!’ (or some variation) making it obvious that they believe DJs ‘remix’ songs on the spot, creating a new version of a song by laying an acapella over another track that they’re creating live. Nine times out of ten what’s happening is the DJ is simply playing a remix a producer slaved over in the studio for a few weeks…it’s just a remix that particular club-goer hadn’t heard before.

There are exceptions. Joe Claussell is a New York-based DJ who constantly manipulates the music he’s playing. He’ll often have a drum track looped while he twists a knob on his mixing desk in quick rhythmic stabs, teasing the crowd with chopped-up, filtered hints of a vocal track before bringing it in fully.

In Toronto, Deko-ze is a DJ I’ve watched keep four tracks running simultaneously, mixing and matching elements from all of them, looping a beat on a CD deck in front of him while reaching off the to side to nudge a record like a plate spinner sensing the need for a slight adjustment.

Some laptop DJs running Ableton Live are able to perform in a similar way because the software has the flexibility to loop a section of one track while the DJ chooses sections of other tracks to bring in, however the need to develop the physical skill of matching the speed of two tracks is eliminated because the software does it for them.

What the audience needs to understand is that a DJ spinning vinyl or CDs cannot separate individual parts of a track unless they’ve been supplied individually on a single or a bootleg. In other situations the best they can do is filter out the bass in a track to clear away some drums and expose the vocal a bit more, or filter out the treble to do the opposite. DJs that are acrobatic enough to have 2, 3 or 4 tracks spinning simultaneously are often layering drums on CD decks (they’re able load a perfectly looped section into memory), adding an acapella they obtained somewhere, and possibly adding musical elements from an instrumental mix of another track. It’s possible to go back and repeat a section of a vocal, or something relatively simple like that, but it’s difficult to apply rapid-fire effects to a vocal. Often you’re hearing something that’s on the acapella already, or the DJ has done some preparation of the track at home first.

What the great majority of DJs do is play one track after another, and the only time more than one element is being heard at the same time is while the DJ is fading from one track into the other, making use of the drums-only intros and outros tacked onto virtually every club track available today. Essentially, club tracks are designed like Lego blocks. The next one snaps onto the last one in most any configuration. It’s known as ‘Train Wrecking’ when a DJ messes up by letting two drum tracks get out of sync with each other while fading from one track to another…because, ostensibly, it sounds as messy as a train going off the tracks.

Club audiences have splintered into as many genres as house music has fractured into. And a DJ that only needs to play one genre, like dubstep or electro, doesn’t have to worry too much about the tracks they play being wildly different in tempo, rhythm or sonic range. Within this realm, the difference between a good DJ and a bad DJ is their taste in tracks, and their ability to read a crowd.

On the extreme side of DJ laziness is Israeli superstar DJ Offer Nissim, who is rumoured to put on a full-length CD created in the studio beforehand and pretend to mix all night from one track to another, collecting a $20k cheque at the end for showing up and ‘performing’!

In the early 90s, when turntables were the only sound source and DJs would begin a night with R&B and rap, progressing to house and eventually hard techno by the end of the night, the DJ had to work hard to learn what worked and what didn’t. Those turntables didn’t have as wide a pitch adjustment range as technology offers now, so beat-mixed music would have to change tempo incrementally over a few tracks.

Some all-but-lost creative mixing techniques include ‘braking’ (hitting the Stop button on the turntable to slow one track dead and then starting the next one, a technique used to start a set in a different tempo) and the ‘hard cut’ (where a DJ would surprise the crowd by cutting from one track directly into another). Hard cuts were sometimes necessary because tracks didn’t always begin with long drum intros…keyboard or acapella intros were acceptable on a 12″ version and this required the DJ to get a little creative.

One of my favourite creative mixes exists on a mixtape made by Toronto’s Patrick ‘D-Nice’ Hodge in 1992. It’s somewhere between a regular crossfade and a hard cut:

At 0:23 the piano riff that comes in is from the next record, ‘Back To Me’ by Ubiquity. This riff is in the same key as the previous record, and it works beautifully with the existing chord progression we’ve been listening to. At 0:31 he drops the first record entirely, as the beat comes in on the new record. The fact that he recognized these two records in his crate would work together in this way is one of those happy accidents that happen increasingly often the more attuned a DJ gets to his material. The second track coming in, by the way, is just slightly flat, because at that time in order to line up the tempo of two recordings, the original pitch of the recordings would slide around as necessary. That’s no longer an issue with CD decks and laptops.

I still don’t know what track Patrick was mixing out of here. If anyone can identify it, please hit me with an e-mail.

Continuing back in time to the mid-70s when DJs like Tom Moulton in New York discovered disco’s relentless ‘4-on-the-floor’ kick drum pattern, the concept of beat-matching two tracks while mixing from one to the other was born. It’s worth mentioning that at that time there were even greater physical challenges for the DJ. Most of these tracks were not recorded at a stable tempo, so the DJ was constantly adjusting the turntable to keep the beat aligned, especially if they were trying to keep two songs running together for more than a few seconds. DJ turntables with convenient pitch sliders and robust tonearms/needles hadn’t been developed yet and neither had 12″ singles with extended versions that had long drum breaks for mixing.

Moulton was reportedly the first DJ to make long versions of his favourite songs by editing them on reel to reel tape and bringing the machine to the club that night. Some of his re-edits were later released by the original labels. I also have it on good authority that at Studio 54, staples like ‘Come To Me’ by France Joli would be extended manually by the DJ by mixing back and forth between two copies of the same record. DJing was a highly physical act at the time, and within the technical limitations there was quite a bit of creativity going on.

Addiction: Fred Everything ft. Wayne Tennant – ‘Mercyless’

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing, Production on May 19, 2009

Wayne Tennant was the lead singer of Toronto funk band God Made Me Funky, then he moved to Montreal, started recording some solo work and spent some time playing Morocco and recording in the UK.

He’s done a collab with Montreal deep house producer Fred Everything for Fred’s album ‘Lost Together’ (Om Records). The track is called Mercyless…the single hit #2 this week on Traxsource…the only soulful house online store that matters. Tastemaker DJ/producer Osunlade also has it in his top ten right now.

Here’s a sampler of the mixes on the single. In order: the original LP mix, then the deeper Fred Everything & Olivier Desmet Remix, then the smooth AtJazz remix.

It’s a slow-burn. I liked it on first listen…I was addicted to it after a few. Wayne’s solo EP is coming out this summer.

Pan & Throw

Posted by Gavin Bradley in DJing, Mixing, Remixing, Singing on May 19, 2009

This blows my mind every time I listen to it:

What you’re listening for is a 16-bar section toward the end of ‘Luv Dancin’ by Underground Solution…circa 1991. Classic house music on the legendary Strictly Rhythm label. The main hook of the track is a female vocal sample from Loose Joints’ disco classic ‘Is It All Over My Face’. There is a version with a full female vocal as well. But there’s a male vocal snippet from the Better Days Remix of Carl Bean’s ‘I Was Born This Way’ weaved into the tapestry and in this part of the extended version the producer decides to riff on that sample for a minute before winding down and man it gets me every time.

It’s partly the sample itself. It’s got that gospel depth to it…he’s feeling that shit…and the way he ends his phrase, trailing down, to a gritty release…there’s tragedy there.

But there are also choices that the producer and/or mix engineer made: the sample pans left and right, sometimes it’s ‘dry’ (no effects), sometimes there’s a delay throw (certain syllables echo) and sometimes there’s a reverb throw (a big roomy sound on it). The patterns entrance me. So simple, yet so complex. So inspired, so not systematic. I could loop those 16 bars all day.

Jane Siberry On Art, Science & Love

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Writing on May 19, 2009

Her voice is often considered quirkily annoying by casual listeners, and in the early 90s, shortly after the career stride of being invited to work with Brian Eno at Peter Gabriel’s RealWorld studios, she played a festival in England and her quirkiness got her booed off the stage. And, in the mid-90s I collaborated with her, shattering all illusions that my high school idol was a person I would want to be friends with.

However.

She was not only a guiding star for me in high school (living in Ottawa but wishing I was safely in her Toronto) but when I go back to her output from ’84-’94, it was quite a contribution to music. Much of her earlier stuff was analytical and humorous, full of casual commentary on art, science and psychology…running with what Laurie Anderson started. When a more serious, personal song appeared in the middle of an album it was surprising that the same person who just discussed the symmetry of atoms in a molecule, or the purpose of non-dancers taking dancing classes, would in the next breath express the bare pain of a breakup.

In ‘You Don’t Need’ she gets poetic, exposing her inner Robert Frost: ‘so I walk on through the marshes and my cheeks are burning white, and my hood is your rejection and my pain is your connection…and a bird I don’t recall called don’t recall called don’t recall…and I know you must be there because people stop to talk to you…you don’t need anyone to want you, don’t want anyone to need you and I think I have yourself almost convinced I have yourself almost convinced…so I ate a star from the far back black sky and it floated up behind one eye and wavered there.’

In the mid-80s, her refreshing, highly conceptual live show was a total girl-fest. It featured three female background singers whose abstract miming was loosely choreographed, and it seemed to be a requirement that they match her oddly wavering vocal style. When the four of them wavered together, it was like four flickering candle flames that synced up unexpectedly for breathtaking moments of harmony, like in the live version of ‘Map Of The World (Part 1)’. There’s a brief reference to Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hey That’s No Way To Say Goodbye’ in the middle of this version, and the payoff comes as the womens’ voices fan out together in a beautiful chord.

After 1993’s ‘When I Was A Boy’ for Reprise records (which included her collaboration with Eno), songs found placements in films and TV shows; Siberry cut a jazz album; she parted with the U.S. major and formed her own indie, Sheeba Records; pioneered pay-what-you-can/’self-determined’ pricing for internet downloads before Radiohead did it; sold signed stuffed rabbit dolls online; disposed of the majority of her earthly belongings including her house; changed her name to Issa Light and continued recording, sessions funded by fans.

Press on sister.