Archive for category Writing

People In Your Neighbourhood

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Labels, Management, Singing, Writing on July 15, 2009

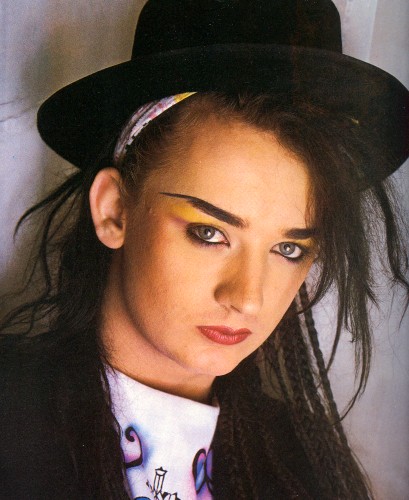

At the height of Culture Club’s success I remember people complaining that Boy George should have been able to make it solely on musical talent, without needing to resort to gimmickry…ie dressing in cosmopolitan drag. He was a talented writer and singer, but–consciously or unconsciously–he realized that audiences are not attracted to artists purely on the merit of their musical output.

We know this is true because there are endless examples of uniquely talented musicians that never garner a substantial following. That’s because what actually attracts us, as listeners, I believe, is an artist’s identity.

It’s true that this identity is built in part around the style and content of the songs, including the lyrics and the overall tone/sentiment. But for a star to be born, it’s critical that the music align properly with a host of other attributes, including the voice they were born with and the way they choose to use it; the physicality they were born with and how they choose to dress it up; how they move; and how they interview. The persona constructed with these tools needs to be instantly recognizable and compelling. (I won’t go so far as to say ‘appealing’, because there are plenty of celebrities that we love to hate.)

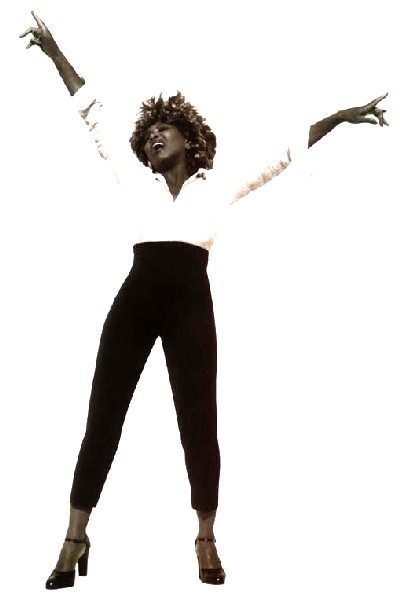

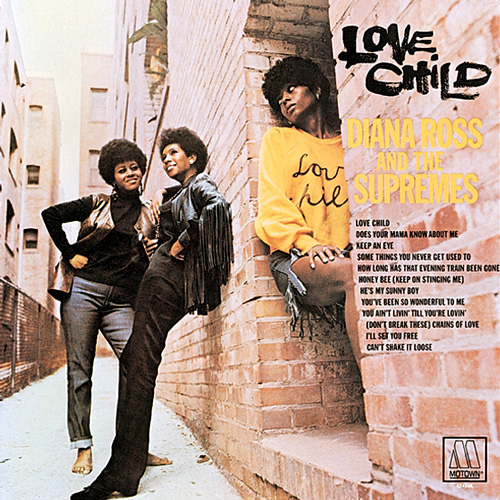

Speaking recently of the Supremes, Diana Ross wasn’t the lead singer of the group because she had the best voice in a technical sense. But her effervescent look and pastel-sounding voice combined to make her a compelling figure: she had instant identity.

Whether it’s the first few lines of a song, or a photo in a magazine spread, the audience needs to get a sense of the artist’s identity similar to the impressions we form of the people in our neighbourhoods we see around but haven’t had personal conversations with yet.

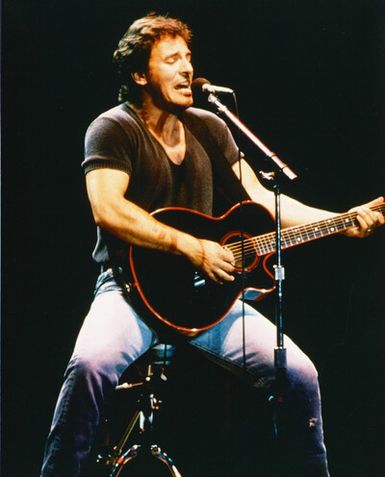

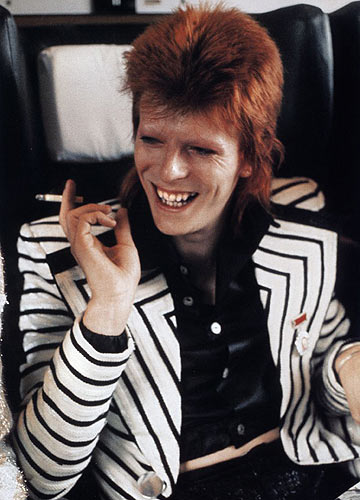

Here are some artists with identities so clear and compelling, whether we like them or not we all feel as though we know them from around.

All musicians are driven to make music. Those that are also driven to author every aspect of their public persona–from clothing to video treatments–end up having a lot less time to sleep but they have an edge over the rest, both in terms of career control and potential for success. That’s because most of us lack the ability to stand back and get a clear perspective on who we are, pinpoint what’s compelling about ourselves and amplify it.

Those who can’t must rely on industry executives’ abilities to look inside them and tailor the right persona…a rare feat in itself. If they get it wrong, the project will fail either because the identity won’t be compelling, or the artist won’t be able to carry an ill-fitting persona for very long before the audience sees through it.

Love Child: Songwriting Economy

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Radio, Writing on July 4, 2009

When you’ve written a good hook it’s natural to want to repeat it as much as possible. It’s also natural to assume that the goal, by the end of the song, is to leave the listener fully satiated.

But if they’re satiated, what’s the motivation to start the song over for another listen? And that’s what you want, isn’t it? A song people can’t get enough of?

Of course dancefloor producers and rock bands have explored the journey-within-a-song aesthetic to great effect, creating many masterpieces over five…seven…even ten minutes long. But if you’re learning to write and you want to reach a lot of people with your music, it pays to set aside the notion that a magnum opus will come out of you before you learn the craft of writing economically.

So, if there is a very special moment in a song, consider not repeating it. Focus instead on coming up with another great melodic moment somewhere else in the song, and don’t write extra verses just to beat the subject matter to death lyrically. Give the listener a reason to put your song on repeat.

When it comes to songwriting economy I can think of no better example than ‘Love Child’ by Diana Ross & The Supremes.

Clocking in at 2:59 the song is a good 10-20 seconds longer than many Motown singles, but that’s probably because there’s enough character and story development in there to write a screenplay.

Released in 1968, the song appeared at a time when writers other than mainstays Holland-Dozier-Holland were being brought into the Motown fold; a time when the label was making a point of moving from innocuous ‘going steady’ lyrics to more socially conscious subject matter.

‘Love Child’ tells the story of a girl who is refusing to take the chance of becoming pregnant by her boyfriend–asking him to wait until they’re married–because she herself was born to an unwed mother, suffering discrimination as a result. The notion of living with the shame of being a ‘love child’ is a bit dated now. But at the time it was edgy material, and the song retains a cooled-out stylistic timelessness.

The economy of the writing is astounding. In just a few sentences we find out who she is; what she and her mother went through; what her father did; what her boyfriend wants from her; what the baby they might have would go through; details around the argument they’re having; and that she knows she’ll always love her boyfriend even if she loses him over her non-negotiable stand:

Love Child

(Pamela Sawyer/R. Dean Taylor/Frank Wilson/Deke Richards)

Prechorus 1

You think that I don’t feel love, but what I feel for you is real love. In those eyes I see reflected a hurt, scorned, rejected…

Chorus 1

Love Child, never meant to be, Love Child, born in poverty, Love Child, never meant to be, Love Child, take a look at me

Verse 2

Started my life in an old cold run down tenement slum. My father left, he never even married mama. I shared the guilt my mama knew, so afraid that others knew I had no name

Prechorus 2

This love we’re contemplating, is worth the pain of waiting. We’ll only end up hating the child we may be creating

Chorus 2

Love child, never meant to be, Love Child, scorned by society, Love Child, always second best, Love Child, different from the rest

Break/Bridge

Hold on, hold on…Hold on, hold on…

Verse 3

I started school in a worn, torn dress that somebody threw out. I knew the way it felt to always live in doubt, to be without the simple things, so afraid my friends would see the guilt in me

Prechorus 3

Don’t think that I don’t need you. Don’t think I don’t want to please you. But no child of mine will be bearing the name of shame I’ve been wearing

Chorus 3

Love Child, Love Child, never quite as good, afraid, ashamed misunderstood

Tag

But I’ll always love you. Wait, won’t you wait now, hold on. I’ll always love you.

‘Love Child’ has no first verse. In an uncommon but inspired move, the writers decided to cut to the first pre-chorus after the song’s short intro. As the pre-chorus is a tension-builder, this serves to set an urgent tone immediately, as opposed to the methodical feeling of beginning with a verse, or giving the mystery away by beginning with the chorus.

Aside from a few poetic descriptive phrases like ‘old cold run down tenement slum’ and the outdated ‘scorned by society,’ the song is written in plain english. In the opening line (‘you think that I don’t feel love, but what I feel for you is real love’) there is no attempt to select ornate, profound-sounding language…but in a short series of single-syllable words we learn what’s happening under the surface: her boyfriend is trying to pressure her into having sex by accusing her of being emotionally unresponsive, while she asserts that the act of waiting to have sex is a manifestation of real love.

Because this song comes in at less than 3 minutes, and because each and every line is a hook unto itself, even maximizing opportunities to fill in the storyline in the choruses with phrases cleverly disguised as ad libs, it’s one of those singles that begs repeated plays. This is when radio happily puts a single into high rotation, and this is when an audience chooses to spend their time listening to a particular artist’s work…rather than the artist having to cajole them into it.

The Cold-Warm Effect

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Production, Singing, Writing on June 18, 2009

After the sound of monophonic synthesizers, played by hand one note at a time, became commonplace on progressive rock recordings in the early 70s…

After people got used to hearing tapestries of synths triggered like clockwork by unfeeling sequencers and arpeggiators in the experiments of Kraftwerk through the mid 70s…

And after producer Giorgio Moroder pulled late-70s disco into the future by placing Donna Summer’s operetics over a pulsing synthetic backdrop on ‘I Feel Love’…

…Alison Moyet belted ‘Goodbye 70s’ over Vince Clark’s minimal synth and drum machine programming on Yaz’s 1981 debut album ‘Upstairs At Eric’s’.

Clark, the keyboard player and chief songwriter for a fledgling Depeche Mode, left the band after their debut album and formed Yaz (known in the UK as Yazoo). Clark’s working relationship with Moyet also imploded early on, leaving just two beautifully crafted Yaz albums. The detached lyrical attitude was new wave and the melodies were pure pop, but the juxtaposition of the warm human soul in Moyet’s ferociously large voice over top of Clark’s frigid production was a new level of what I call ‘cold-warm’ production.

‘Midnight’ is a great example of this style. After a naturally-paced acapella intro, the synth sequence begins without drama or fanfare. Emotionless and ruthlessly precise, it’s there solely to do the job of defining a framework of chords and rhythm under her voice. Her delivery is suddenly recontextualized: because the backdrop is icy cold, the heat of human breath against it is that much more apparent.

After Yaz, Moyet began a successful solo career and Clark formed Erasure with Andy Bell–whose vocal tone, it has been noted, is curiously similar to Moyet’s.

Enter Eurythmics. Dave Stewart and Annie Lennox had been making music together for some time, first in rock band The Tourists and then as Eurythmics, releasing their experimental but mostly organic (ie non-electronic) debut album ‘In The Garden’ in 1981.

But then they clued in on where Yaz, and other UK synth-based bands like The Human League and Heaven 17 were going and jumped in on their seminal ‘Sweet Dreams (Are Made Of This)’ album in 1983.

The liner notes on the 2005 reissues of the Eurythmics’ catalog discussed which drum machines and synths had been used, and also revealed that organic sounds–like drumming on glass bottles–were routinely weaved in. However, these were treated with effects so as to be camouflaged as part of the cold electronics. A manifesto of the pair’s directives was written on the wall of their studio, including the phrases ‘Tamla Motown,’ ‘Electronica’ and ‘Coldness’. So there it is: soul on ice.

On their best work–the fully electronic ‘Sweet Dreams’, ‘Touch’ and ‘Savage’ albums–Lennox’s soulful voice is generally the solitary human element sitting on top of the coldness. She even sonically evokes the visual of her warm breath meeting wintery cold in her trademark practice of peppering vocal performances with gutteral stabs of exhalation. Very occasionally another warm melodic element is chosen to create that same contrast against the pings and bleeps: the long trumpet solo on ‘The Walk’ and the violin lines of the British Philharmonic Orchestra on ‘Here Comes The Rain Again’.

‘Love Is A Stranger’ is a 3-minute pop song with a perfect balance of soul and circuitry.

Lennox pushed her experimentation with coldness further by developing a suitably cold image. Often labeled androgynous, I believe her main character, sporting an orange crew-cut, would be more accurately described as inhabiting a deadened sexuality. After having established that baseline, she was then in a position to play with the hypermasculine (dressing up as Elvis in the video for ‘Who’s That Girl’) or the hyperfeminine (her female character in the same video, or the split-personality cougar depicted on the ‘Savage’ concept album) as a way to critique, humorously, the traditionally accepted extremes of gender.

She also brought a detached, frigid air to many of her lyrics. On ‘Regrets’ she plays a bloodless character listing the chilling powers available to her: “I’ve got a dangerous nature, and my fist collides with your furniture…I’ve got a razor blade smile…fifteen senses are on my palette…I’m an electric wire and I’m stuck inside your head.” After establishing a consistent lack of emotion, lyrically, the slightest hint of tenderness in her lyrics would be magnified tenfold.

It must be said–because it’s not mentioned very often–that much of the groundwork for Lennox’ success was laid by Grace Jones. In fact Jones’ vocal licks and delivery, her ruthless lyrical style and her arty experimentation with androgyny right down to the signature crew cut were clearly recycled by Lennox in the early years of Eurythmics. What Jones lacked was commercial hooks in the songs, and what was special about the Eurythmics was the starkness of the electronic backdrop that Dave Stewart provided, which in my view couldn’t have more perfectly showcased the warmth of the human voice.

Song Structure 101

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Writing on June 14, 2009

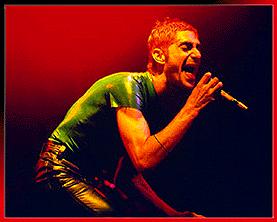

Legend has it that Jane’s Addiction frontman Perry Farrell came up with ‘Been Caught Stealing’ specifically to prove he was capable of–though not particularly interested in–writing radio hits. Of course after the song spent four weeks at #1 and the band made the jump from college dorm buzz to a household name, Farrell had the resources to create Lollapalooza and retire back to writing whatever he felt like writing.

Formulaic writing gets a bad rap. Nobody wants to feel that the music they love was written in a calculated way, but I think it’s important to draw a distinction between upholding the tradition of the 3-minute pop song and completely reverse-engineering music based on market studies. The fact is, for better or worse, every one of us has been programmed to understand a couple of basic song structures.

The main one: Verse–Prechorus–Chorus–Verse–Prechorus–Chorus–Bridge–Chorus

Sometimes there’s a short intro. We expect the first verse to spell out what the song is going to be about. The prechorus that follows builds tension toward an anticipated payoff. The chorus is the catchy main idea that we’ve been waiting for–the repeated part that everyone can sing along to–and it usually contains the song title. (In olden times it was known as the ‘refrain’, and it’s more and more often referred to as the ‘hook’ in the age of hip hop.)

In the second verse the story continues to be told. Expect a new idea or a new perspective to be introduced, just when it might start getting boring. Lyrics are almost never repeated in verses. The prechorus that follows may contain the same words as the first, but it may be shortened to get to the second chorus faster. Next, three quarters of the way through the song, a bridge (or ‘b-section’) breaks the melodic pattern…it’s somewhere else to go for a moment. Sometimes solos are used in place of, or in addition to, bridges. Finally, we’re taken home with the biggest chorus yet at the end.

Occasionally you’ll get a song with no prechoruses, or one with an outro or ‘tag’ at the end. But this basic structure applies to virtually every song you’ve ever heard. Even long club mixes are the same: there’s just a longer intro, a longer bridge in the form of a drum break or build, and a longer outro.

Many new writers are unaware of this structure, or they will intentionally start writing without studying it with the belief that this will allow them to express themselves in a pure way, unfettered by convention. However it’s basically inevitable that when they do hit on a structure that feels right, it will be because they’ve kept moving parts around until they have something that follows the structure described above.

So it’s just faster to accept that this song arc is part of a language we’ve all learned subconsciously. It’s a tradition. There is still plenty of room within that tradition to be an individual. In many ways we should be thankful that the structure pins down a couple of constants for us. What sets writers apart is the substance they fill this pre-determined form with. And the more experienced writers will naturally begin to manipulate the structure in ways that make sense to all of us as listeners.

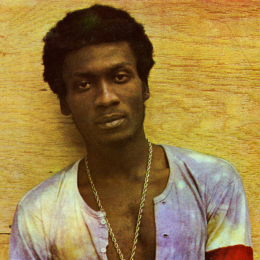

The other song structure worth mentioning is an older form that has its roots in gospel hymns: Chorus–Bridge–Chorus–Bridge–Chorus. Jimmy Cliff made use of its spiritual feel in his classic ‘Many Rivers To Cross’:

Each chorus begins with the lyric ‘Many rivers to cross,’ and from there he identifies another aspect of his tribulations: ‘…and it’s only my will that keeps me alive. I’ve been licked, washed up for years, and I merely survive because of my pride.’ The bridge section, which appears twice to provide a respite from the chorus, addresses his loneliness: ‘But loneliness won’t leave me alone. It’s such a drag to be on your own. My woman left and she didn’t say why. Well I guess I have to cry.’

One of the few songs in the history of pop music that defies convention is Marvin Gaye’s classic ‘Let’s Get It On’. The song does follow Chorus-Bridge-Chorus-Bridge-Chorus form, but the melody is ‘through-written,’ meaning each section takes a new melodic route, with very little repetition. It’s extremely difficult to write something that stays hooky throughout without ever repeating the melody…but if you think you know as much as Marvin Gaye knew about writing when he came up with the seemingly effortless ‘Let’s Get It On’, I encourage you to try it!

Total Deconstruction: Buffalo Stance

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Remixing, Writing on June 3, 2009

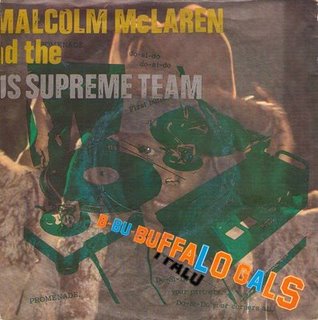

1. In 1982 the Sex Pistols’ manager Malcolm McLaren jumped ship on punk by traveling to New York and appropriating elements of cutting edge hip hop culture on a groundbreaking single called ‘Buffalo Gals’.

2. In 1986 a British duo Morgan McVey released a painfully cheesy pop song called ‘Looking Good Diving.’

3. The duo’s Cameron McVey asked his wife, Neneh Cherry, to come in and rap over an instrumental version of the song. That version was released as the b-side, listed as ‘Looking Good Diving With The Wild Bunch’. (She was a member of the Wild Bunch crew, along with members of Massive Attack.)

4. Oddly, Nick Kamen also recorded a version.

5. In 1988 Cherry’s rap was salvaged–along with the excellent synth hooks from Looking Good Diving–and parts of ‘Buffalo Gals’ were scratched in over a new beat to concoct Neneh Cherry’s seminal single ‘Buffalo Stance’.

6. The song was then remixed to death, in an era when remixing was taking a giant leap. The purpose of a remix had always been to extend a song, perhaps throwing in a little extra ear candy for the dancefloor. But now that you could load the whole acapella into a sampler and access sections of it at will–as opposed to having to run it off of a linear master tape–total deconstruction became the norm.

Dropping the needle on a single like ‘Buffalo Stance’, you heard every familiar nuance of the vocal track over an entirely unfamiliar backdrop…structure, chords and rhythms entirely re-imagined. It took three 12″ singles and one 7″ single to squeeze all the juice out of this track. It was as though the remixers tag-teamed, sampling elements of each others’ versions and riffing on them further.

Below are a series of excerpts: the classic benchmark ’12” Mix’ which was the long version of the original Tim Simenon production; the Dynamik Duo’s sparse ‘Sukka Mix’ containing all kinds of gritty vocal outtakes; Arthur Baker’s ‘1/2 Way 2 House Mix’ which placed the vocal over a mellow house-ish groove before moving on to an abstract collage of vocal samples; Kevin Saunderson’s crunchy ‘Technostance Remix I’ which sort of encapsulated samples of the original version in between dubby loops; and finally Massive Attack’s bizarre disco take entitled ‘There’s Nothing Wrong Sukka Mix’.

7. In 1990 George Michael got his fingers in the pudding by releasing a remix of ‘Freedom 90’ that combined vocals from his original song with his own rendition of Soul II Soul’s ‘Back To Life’. In re-singing it, he lovingly emulated Caron Wheeler’s every phrase. The mix also contained a sample of the fiddle riff from Sinead O’Connor’s ‘I Am Stretched On Your Grave’ and a re-created loop from ‘Buffalo Stance’ (the ‘Buffalo Gals’ scratches and his rip of Neneh Cherry’s ‘Get Funky’). This ‘remix’ (or medley, as it would more accurately be called, since he took this opportunity to sing portions of peoples’ songs) felt like a synchronistic experience for me as those particular songs he chose to combine had all been huge for me that year.

What fascinates me about this evolution is not just the multiple levels of cut-and-paste that went on through these productions, but the fact that this exposes a clear example of the sort of rewriting/rethinking that sometimes must happen before a song hits its apex. Cherry’s rap on the b-side of ‘Looking Good Diving’ isn’t the fully realized version of the lyrics she went with on ‘Buffalo Stance,’ and neither is her confidence in place, yet, vocally.

Chord Progressions: Making People Feel Something

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Writing on May 30, 2009

I always wince when industry execs refer to songs as being emotional…as in ‘let’s hear that first song you played again, the one with the emotional chorus.’ Correct me if I’m wrong, all music is supposed to make you feel something. But what they’re getting at is songs that become the biggest hit singles often have an extraordinarily strong emotional pull.

Melody and lyrics are critical when it comes to emotional pull (and in my opinion a talent for melody is the one thing that a person can’t be taught) but well-written chord progressions are key, and the importance of the series of chords chosen for a song is overlooked by many new writers.

Sitting down with the piano or guitar we often believe that whatever chord changes first came to mind are the foundation of the song; that it’s unchangeable and the task is now to write some words and melodies over top. However in truth you can manipulate the chords under a vocal just as readily as you can manipulate the melody: remixing often involves doing just that. When you stop automatically trusting whatever chords you happened to pick out of the air, you begin to have some control over how the song makes people feel. This is what people refer to as songwriting ‘craft’ and it’s part of getting professional about your writing.

Without getting too far into the dry wasteland that is music theory, here’s a way to open up your writing.

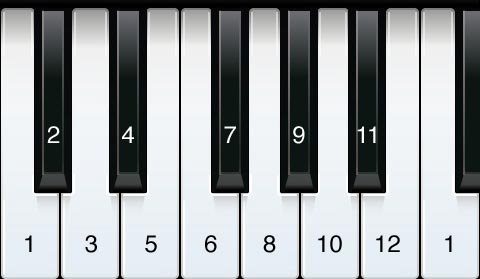

If you sit at a piano and play chords up the scale of C Major, this is what you’ll get:

Position 1 = C major

Position 2 = D minor

Position 3 = E minor

Position 4 = F major

Position 5 = G major

Position 6 = A minor

Position 7 = B diminished

When most people begin writing, they’ll try something basic like alternating back and forth between two chords, say Position 1 (C major) and Position 4 (F major), and they’ll go with that as their verse or chorus. Simple progressions that sound good to our ears tend to become the standbys we go to unless we challenge ourselves. I’ve noticed that some people believe you can only move a step at a time in either direction…creating chord progressions like 1, 2, 3, 2. You can jump all over the place, and you should.

For years I was in the habit of only using the 7 chords readily available in the scale. Until I was shown, I didn’t realize that I could, for example, play a progression like 4 (F major), 5 (G major) and then a minor 5 (G minor, which is not naturally in the key of C) and then 1 (C major) without the earth caving in. In fact, go ahead and move to any chord from where you are. You can move from position 1 to position 4, but use an F Minor instead of an F Major. Or you can play a C Major followed immediately by a C Minor.

When you let go of the scale you’re in and allow yourself to see all 12 notes available on the keyboard you realize that at any given moment, from where you are, there are 23 other basic places that you can go. (The major and minor chords of all 12 notes, minus the chord you’re already on.) Sometime, when you’re sitting at your instrument with no inspiration, I recommend jumping around between chords for a while as a way of opening up your writing. Some of the jumps you’d normally never think to play can spark a feeling you know from other music, but didn’t know how to evoke yourself…and you can find yourself writing a song around the device you’ve just discovered.

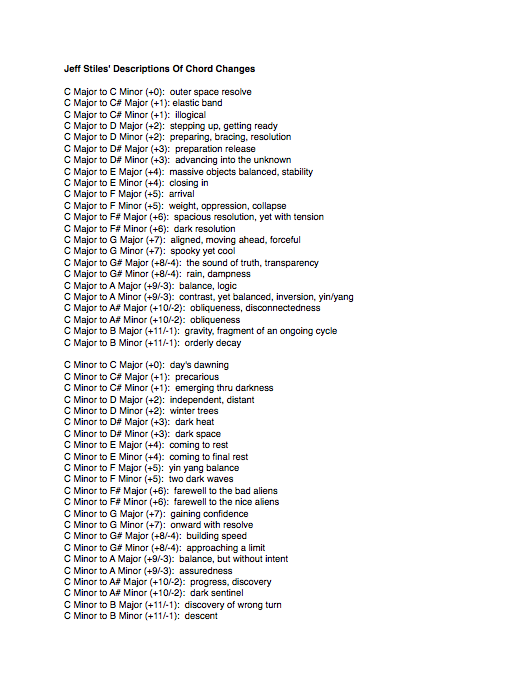

A few years ago I did an experiment with some friends who write. We all separately played C major followed by C minor…and then wrote down a description of how that chord change felt. Then we did C major followed by D major, and all of the other possible jumps moving up the keyboard.

Put side by side, many of our written descriptions described similar emotional responses. Some images that kept showing up were the feeling of ‘stepping up or down,’ (fairly obvious for standard incremental movements along the keyboard like C major to D major); ‘precarious balance’ (for less standard incremental movements like C minor to C sharp minor); ‘optimism’ or ‘pessimism,’ (when the chord change involved changing between a major and a minor); ‘assuredness’ (a common jump like C major to A minor); even ‘planetary’ feelings (for odd longer jumps like a C major to F-sharp minor, which are obviously used in lots of space movies).

So it looks to me like, either by nature or nurture, we feel chord progressions in similar ways. When you’re writing at your instrument and what you’ve got feels okay but not great, I encourage you to challenge one of your chord changes by trying the 22 remaining possibilities. If you do this often enough, you’ll develop a strong command of the emotions you bring as the listener moves through the song with you.

Jane Siberry On Art, Science & Love

Posted by Gavin Bradley in Writing on May 19, 2009

Her voice is often considered quirkily annoying by casual listeners, and in the early 90s, shortly after the career stride of being invited to work with Brian Eno at Peter Gabriel’s RealWorld studios, she played a festival in England and her quirkiness got her booed off the stage. And, in the mid-90s I collaborated with her, shattering all illusions that my high school idol was a person I would want to be friends with.

However.

She was not only a guiding star for me in high school (living in Ottawa but wishing I was safely in her Toronto) but when I go back to her output from ’84-’94, it was quite a contribution to music. Much of her earlier stuff was analytical and humorous, full of casual commentary on art, science and psychology…running with what Laurie Anderson started. When a more serious, personal song appeared in the middle of an album it was surprising that the same person who just discussed the symmetry of atoms in a molecule, or the purpose of non-dancers taking dancing classes, would in the next breath express the bare pain of a breakup.

In ‘You Don’t Need’ she gets poetic, exposing her inner Robert Frost: ‘so I walk on through the marshes and my cheeks are burning white, and my hood is your rejection and my pain is your connection…and a bird I don’t recall called don’t recall called don’t recall…and I know you must be there because people stop to talk to you…you don’t need anyone to want you, don’t want anyone to need you and I think I have yourself almost convinced I have yourself almost convinced…so I ate a star from the far back black sky and it floated up behind one eye and wavered there.’

In the mid-80s, her refreshing, highly conceptual live show was a total girl-fest. It featured three female background singers whose abstract miming was loosely choreographed, and it seemed to be a requirement that they match her oddly wavering vocal style. When the four of them wavered together, it was like four flickering candle flames that synced up unexpectedly for breathtaking moments of harmony, like in the live version of ‘Map Of The World (Part 1)’. There’s a brief reference to Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hey That’s No Way To Say Goodbye’ in the middle of this version, and the payoff comes as the womens’ voices fan out together in a beautiful chord.

After 1993’s ‘When I Was A Boy’ for Reprise records (which included her collaboration with Eno), songs found placements in films and TV shows; Siberry cut a jazz album; she parted with the U.S. major and formed her own indie, Sheeba Records; pioneered pay-what-you-can/’self-determined’ pricing for internet downloads before Radiohead did it; sold signed stuffed rabbit dolls online; disposed of the majority of her earthly belongings including her house; changed her name to Issa Light and continued recording, sessions funded by fans.

Press on sister.